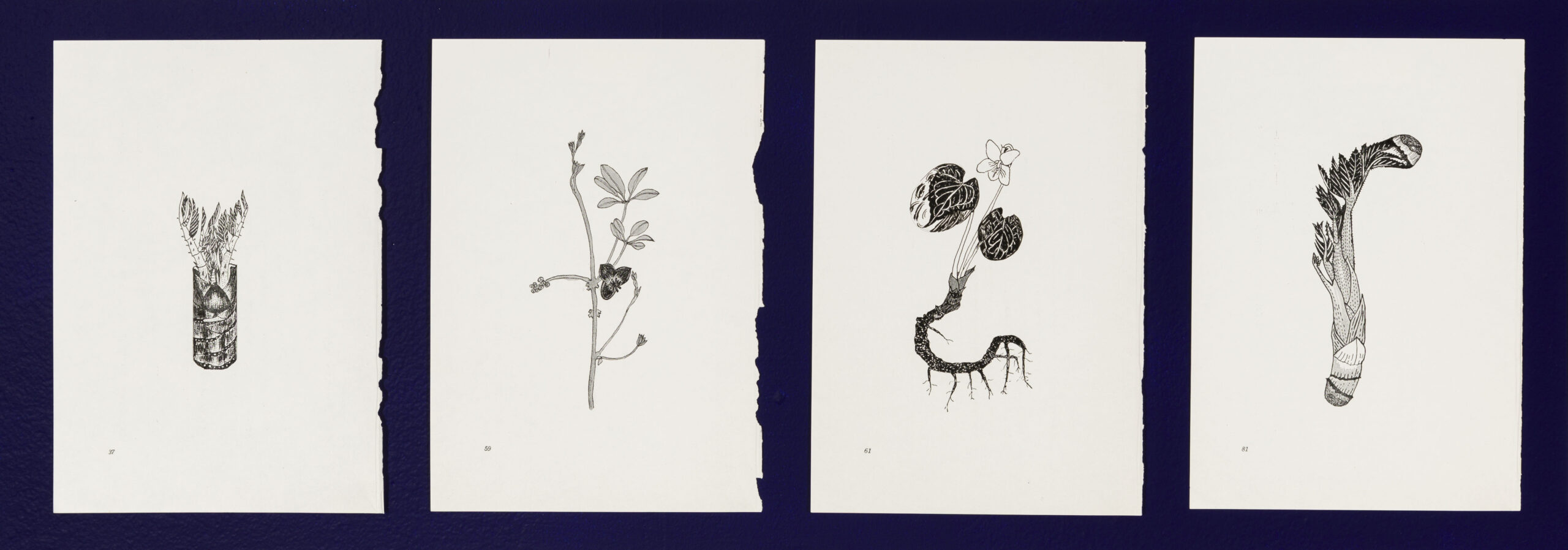

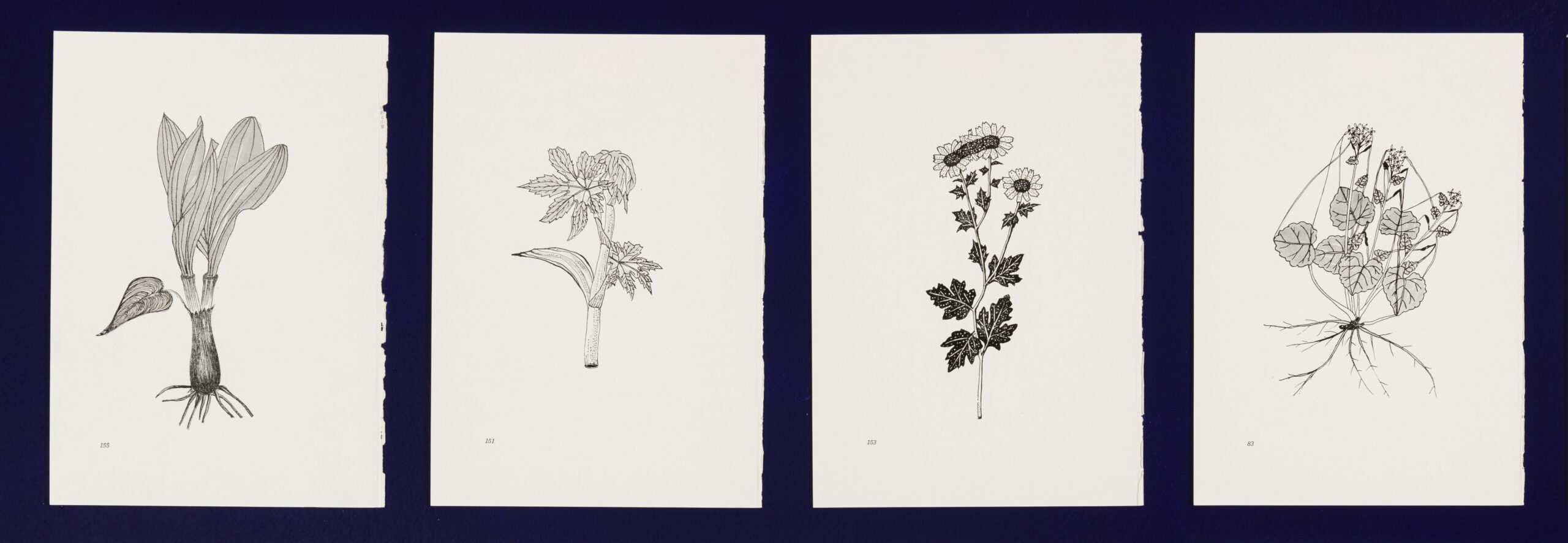

Mutated

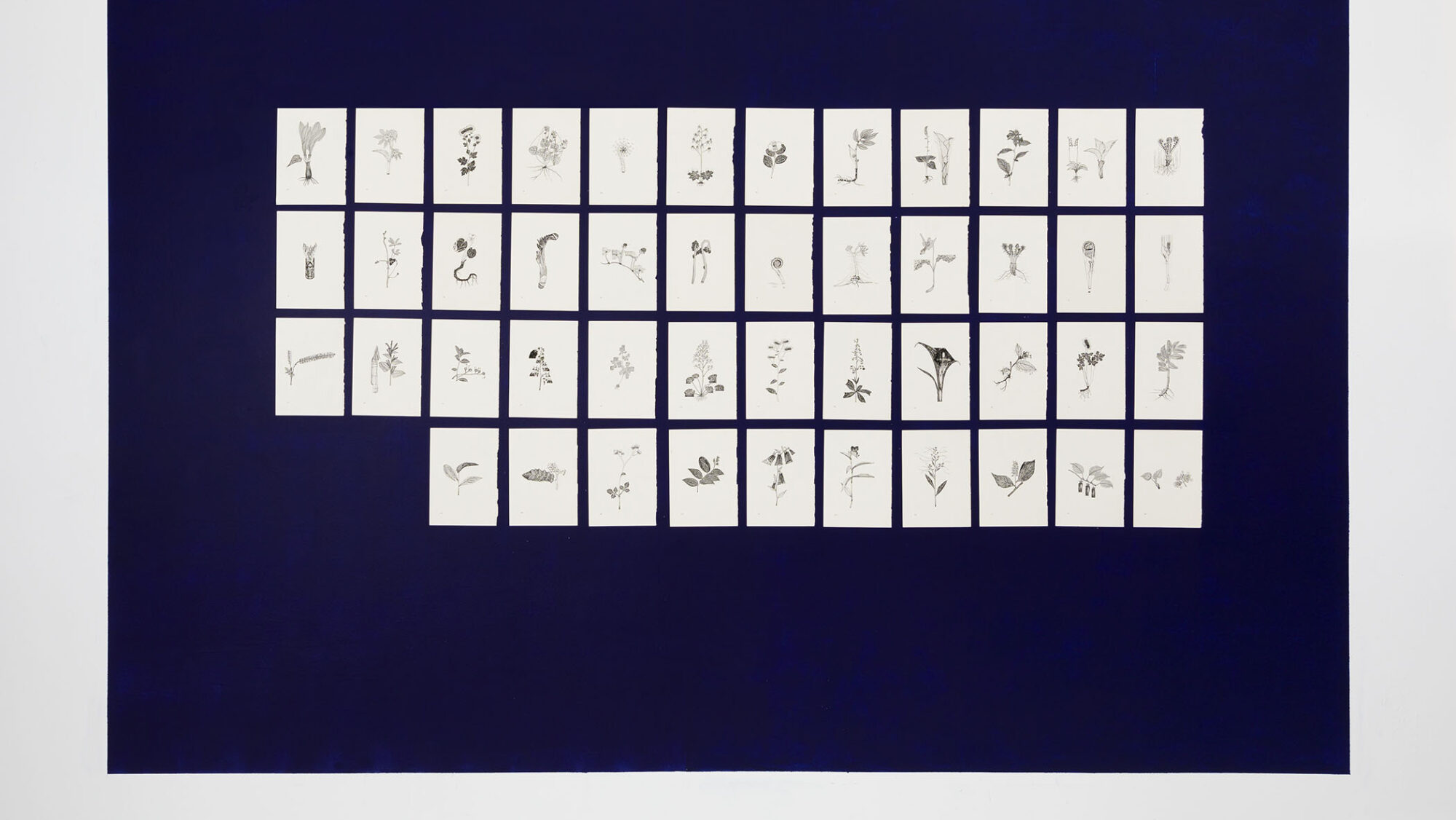

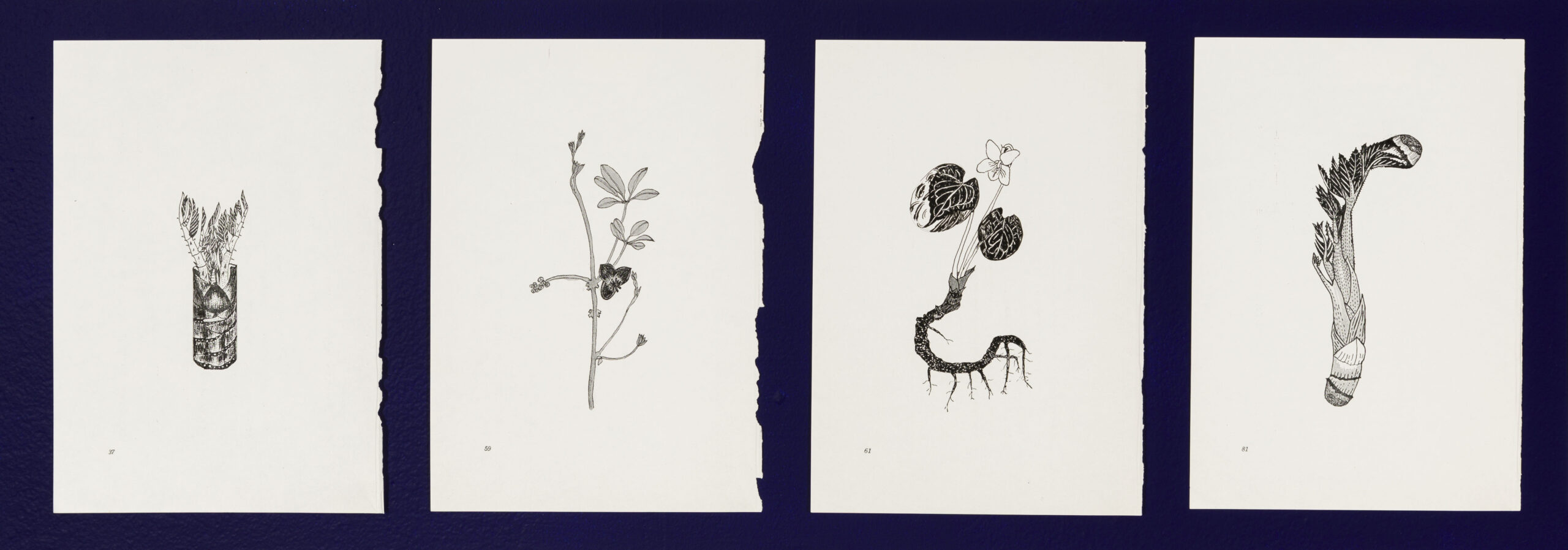

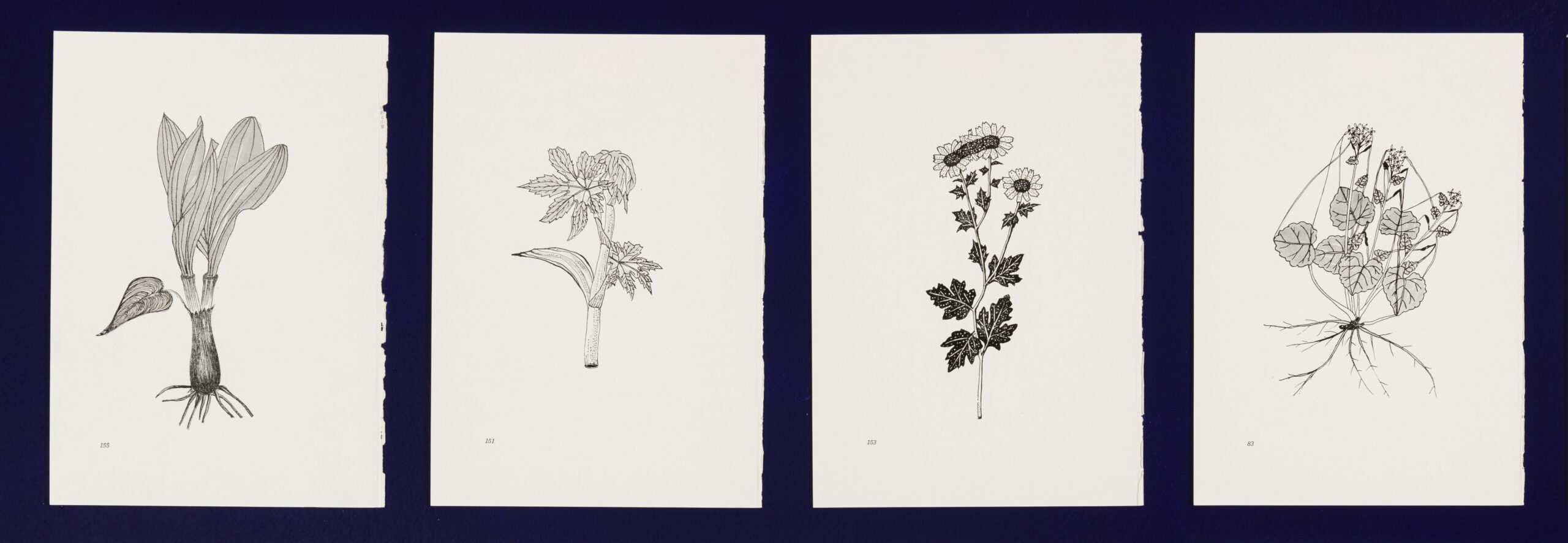

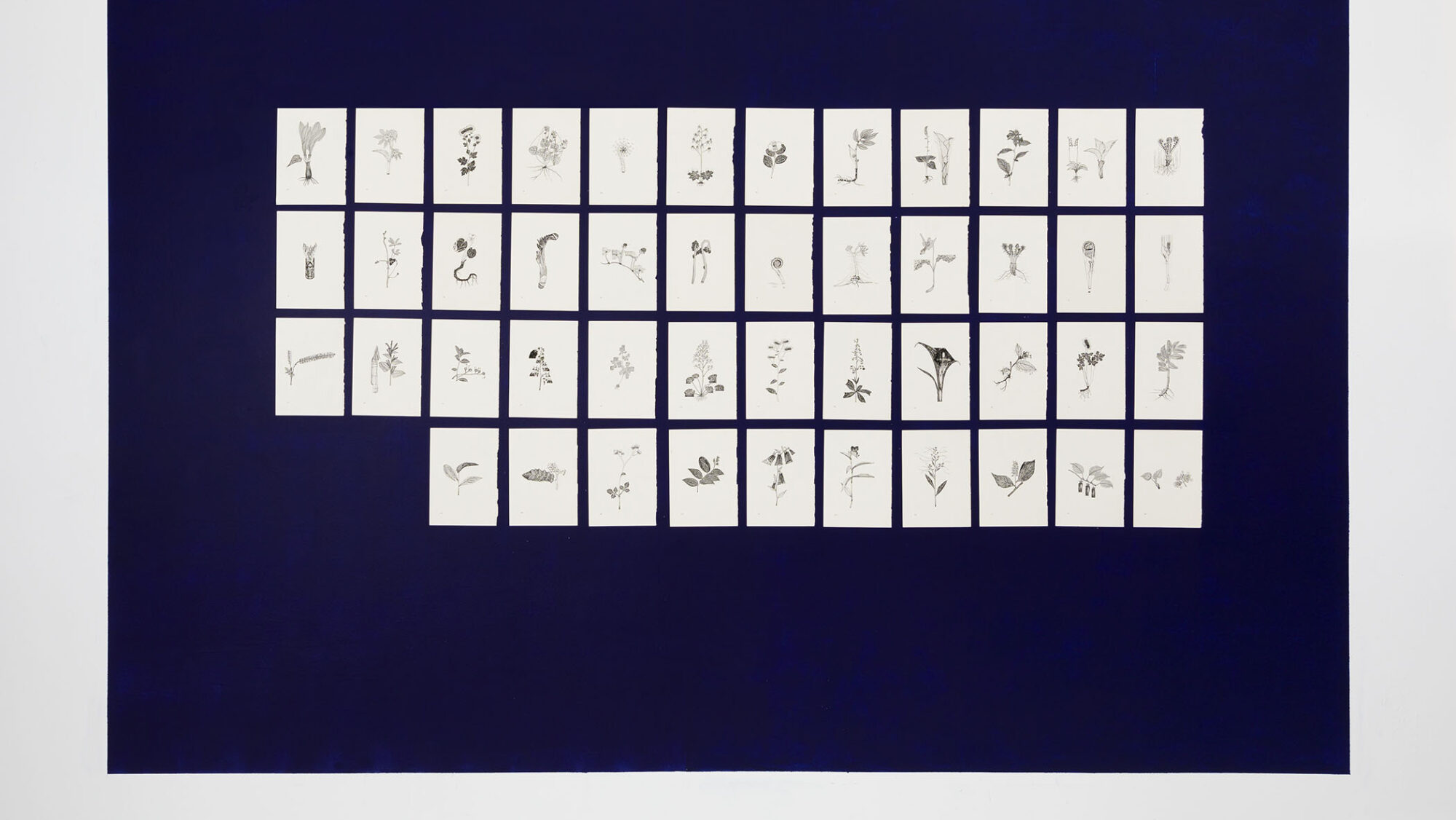

A series of 46 drawings, ink on pages from a found book, 8 1/4 x 5 3/4 in. 21 x 14.5 cm (each) 2017

A series of 46 drawings, ink on pages from a found book, 8 1/4 x 5 3/4 in. 21 x 14.5 cm (each) 2017

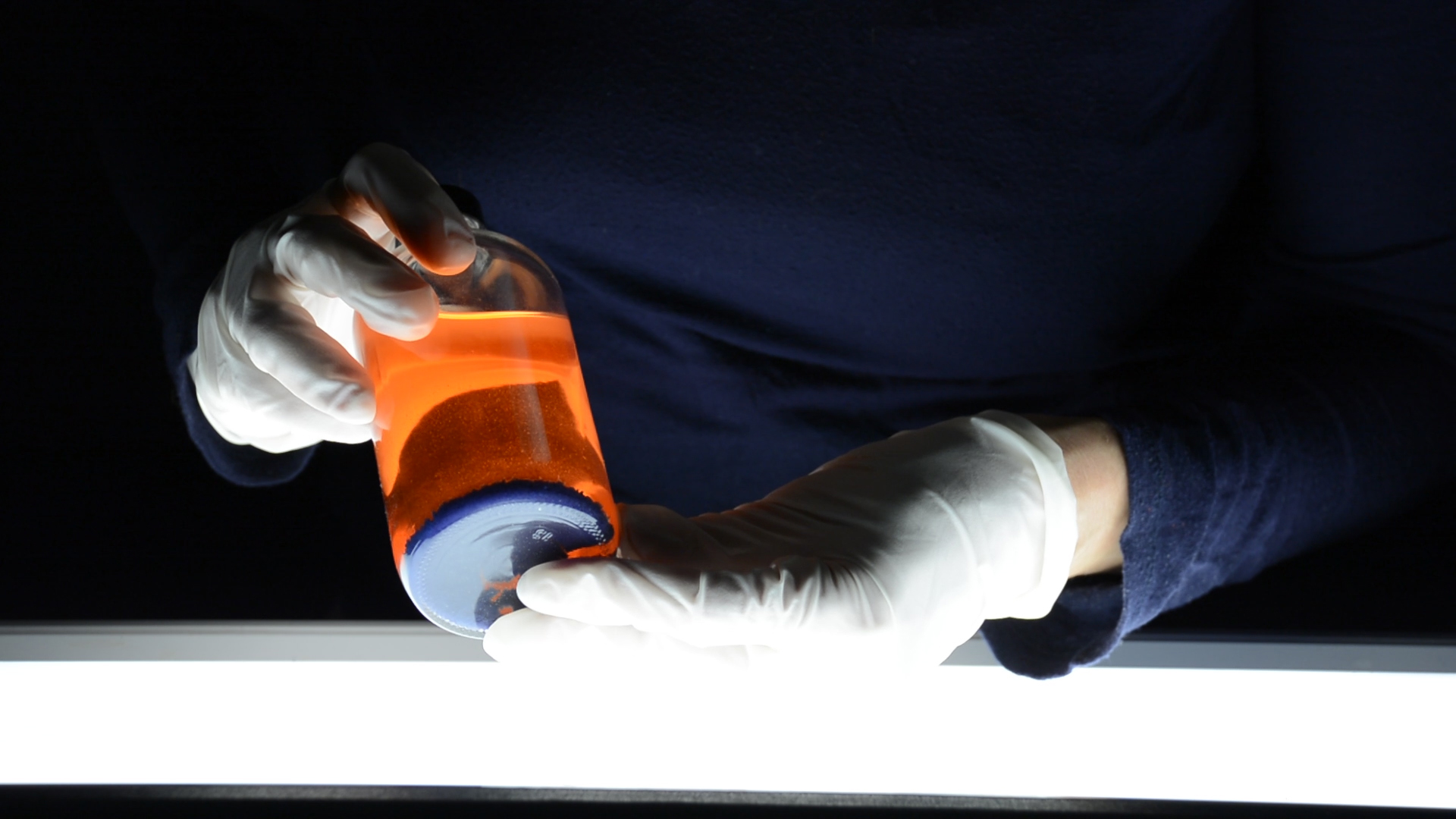

HD Video, Hebrew, English subtitles, 13’30 minutes. 2023

The film, named after a deadly virus in the citrus industry Tristeza (‘Sadness’ in Spanish and Portuguese), documents the artist’s failed attempts to grow a variety of blue oranges, raises questions about migration and belonging and undermines the concept of a homeland.From agriculture to genetic engineering, scientific facts are interwoven into the artist’s and her family’s story as they reflect her conflicts: to stay, to take root, to succeed in changing the DNA of an orange so that it will be its complementary color – blue. The film ends as it begins, with moldy oranges, but this failure produces a new blue orange, and its decaying remains become a series of images – landscapes of the country.

Text: Keren Benbenisty & David Stevens

Voice over: Keren Benbenisty

Image, sound, and editing: Keren Benbenisty

Sound Mix: Quentin Chiappetta

Installation views, Ulterior Gallery, New York, NY, 2024

Conceived as the world was coming to a halt during the pandemic, Keren Benbenisty’s Tristeza II is a poetic reflection on movement that focuses on return to and migration from one’s supposed homeland. Return and migration seem like opposite moves, but disentangling the “leaving” from the “return” turns out to be impossible. Each movement holds, perhaps is even trapped in, its potential opposite.

Tristeza II, a continuation of a 2021 show that Benbenisty named after the same lethal virus that infects citrus trees, comprises a series of new works without a prescribed sequence. At the center is a 14-minute video narrating the artist’s attempt at cultivating a blue orange. The other works in the exhibition also revolve around the orange and expand on themes raised in the video.

Oranges arrived in Palestine in the tenth century and had become an important export commodity by the mid-1800s. In the 1920s and the early 1930s, oranges cultivated by Muslim, Christian, and Jewish landowners were the leading export product of mandatory Palestine. The following decades witnessed a gradual decline of the citrus industry in Palestine, though the fruit retained its significance for both Palestinians and Zionists as a quintessential symbol of ties to the land. For the Palestinians, especially after 1948, the orange became the signifier of the lost homeland – “the land of sad oranges,” in the words of the Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani. For the Zionists, the orange symbolized the return to ancestral territory and the emergence of a new, industrious Jewish state.

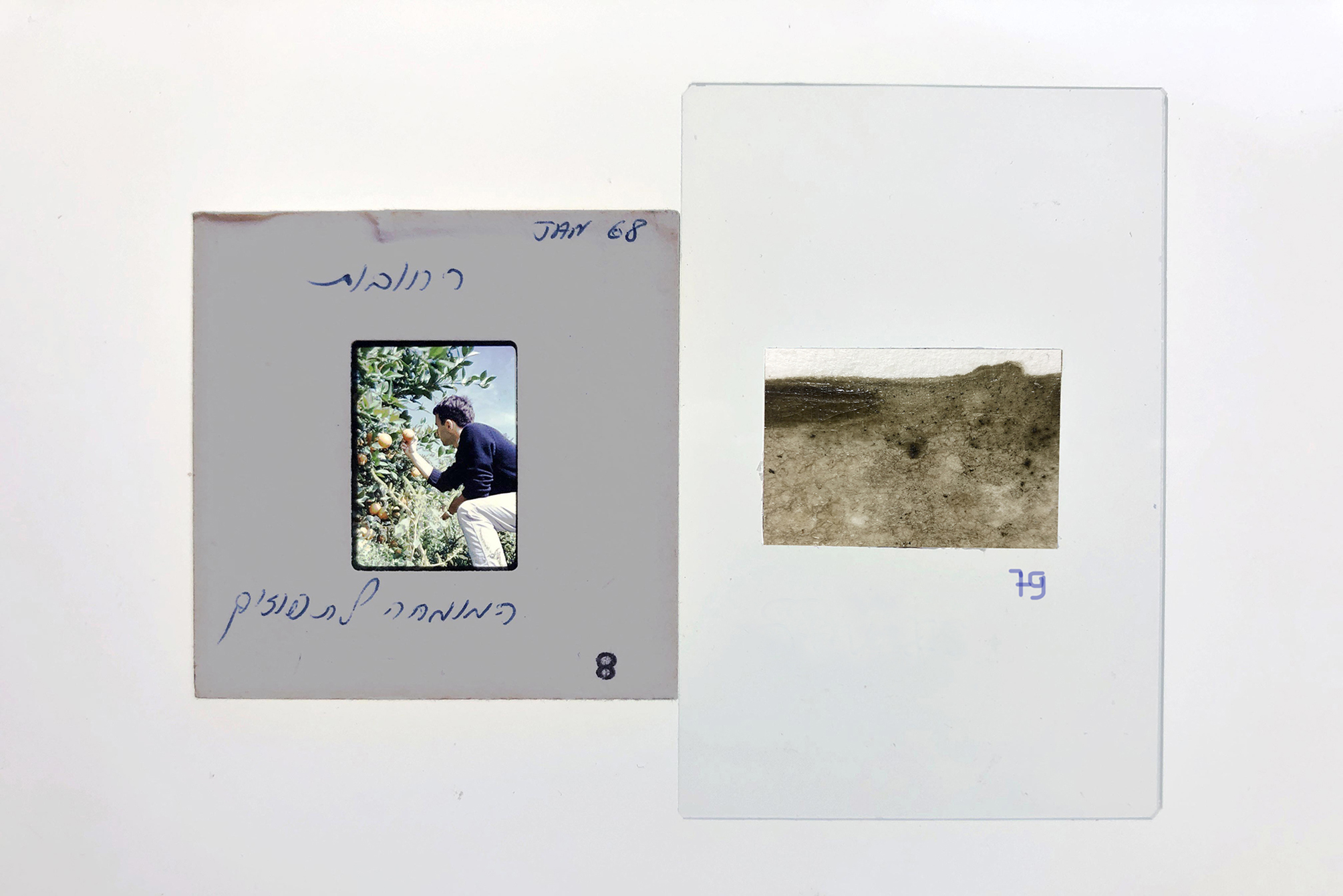

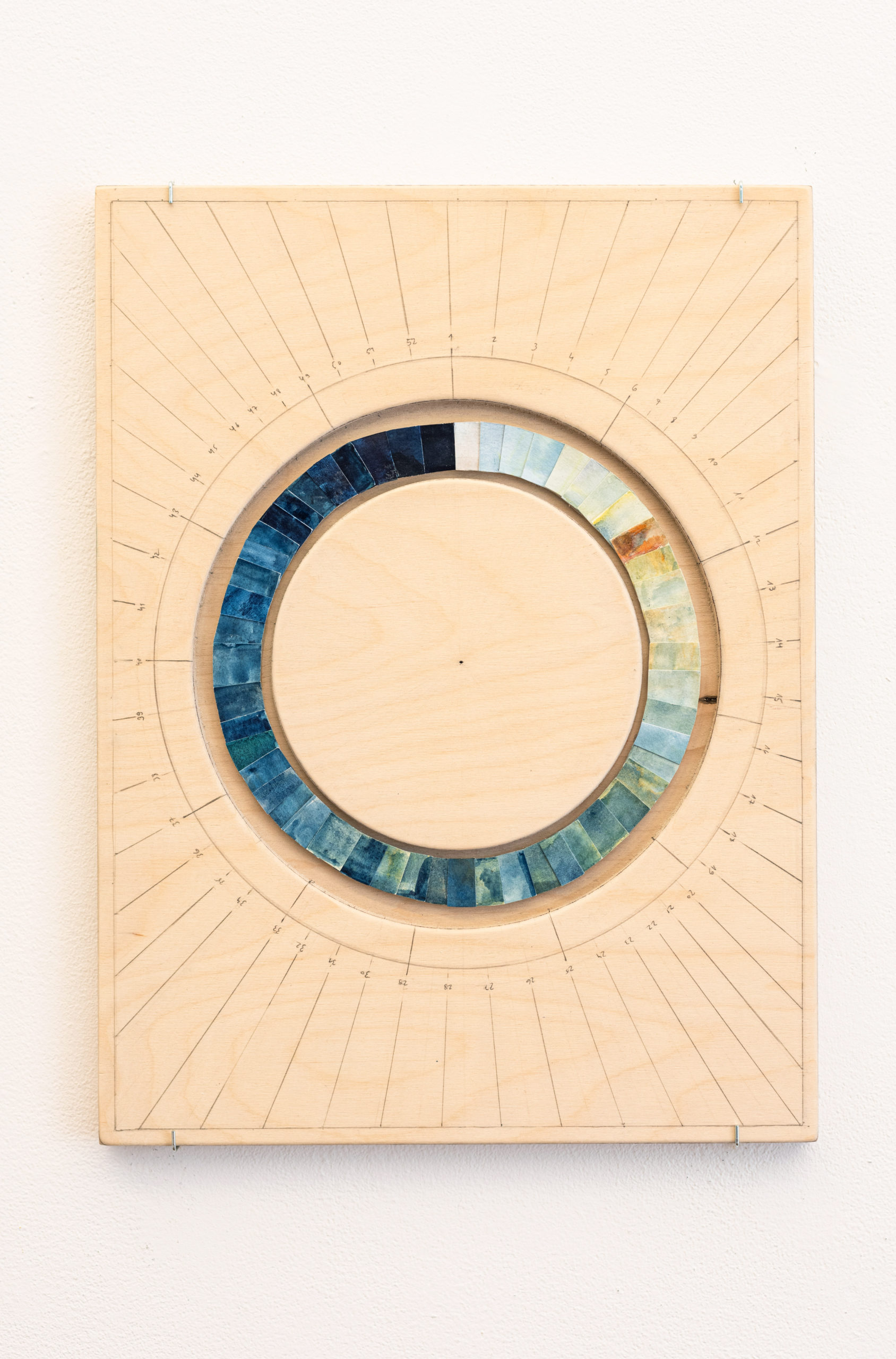

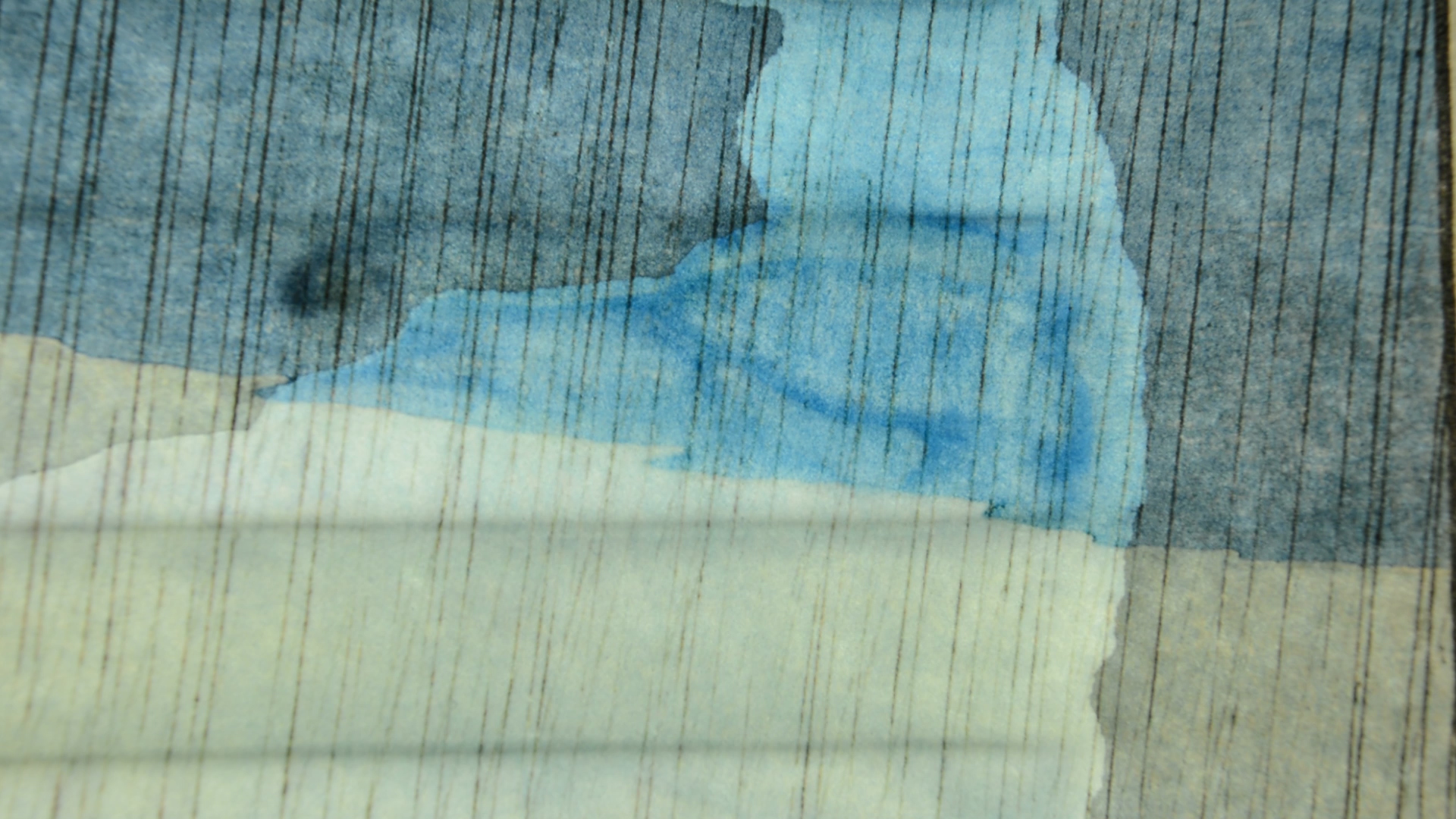

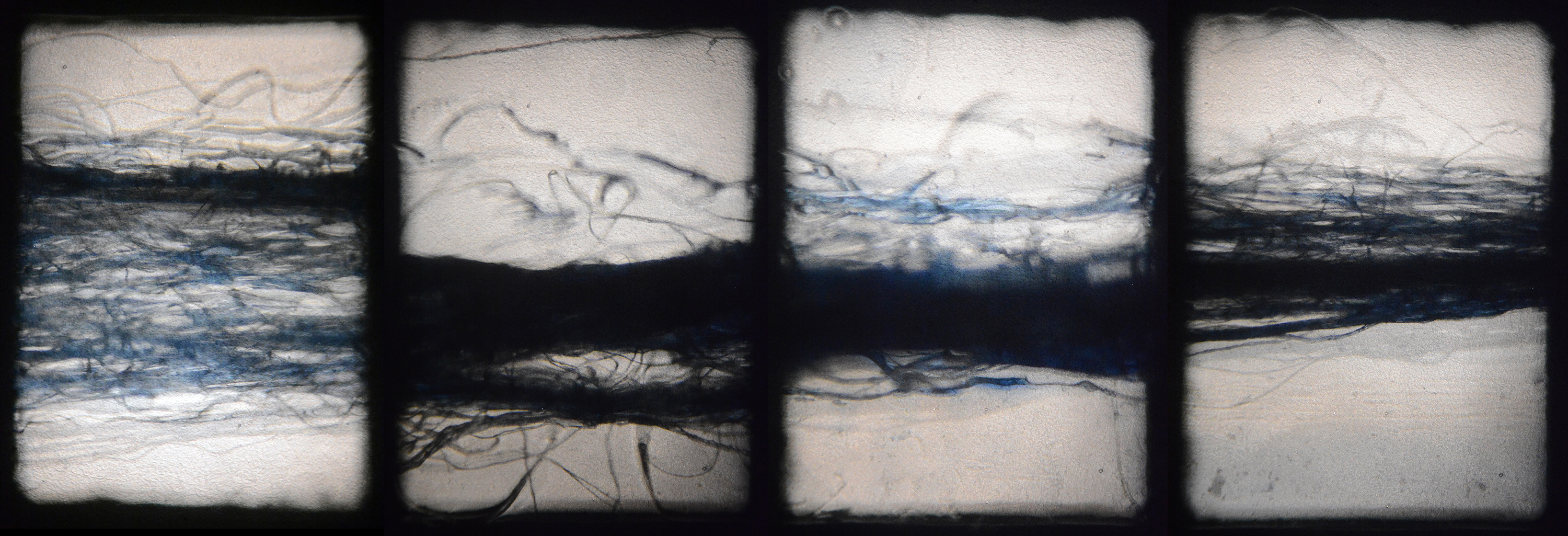

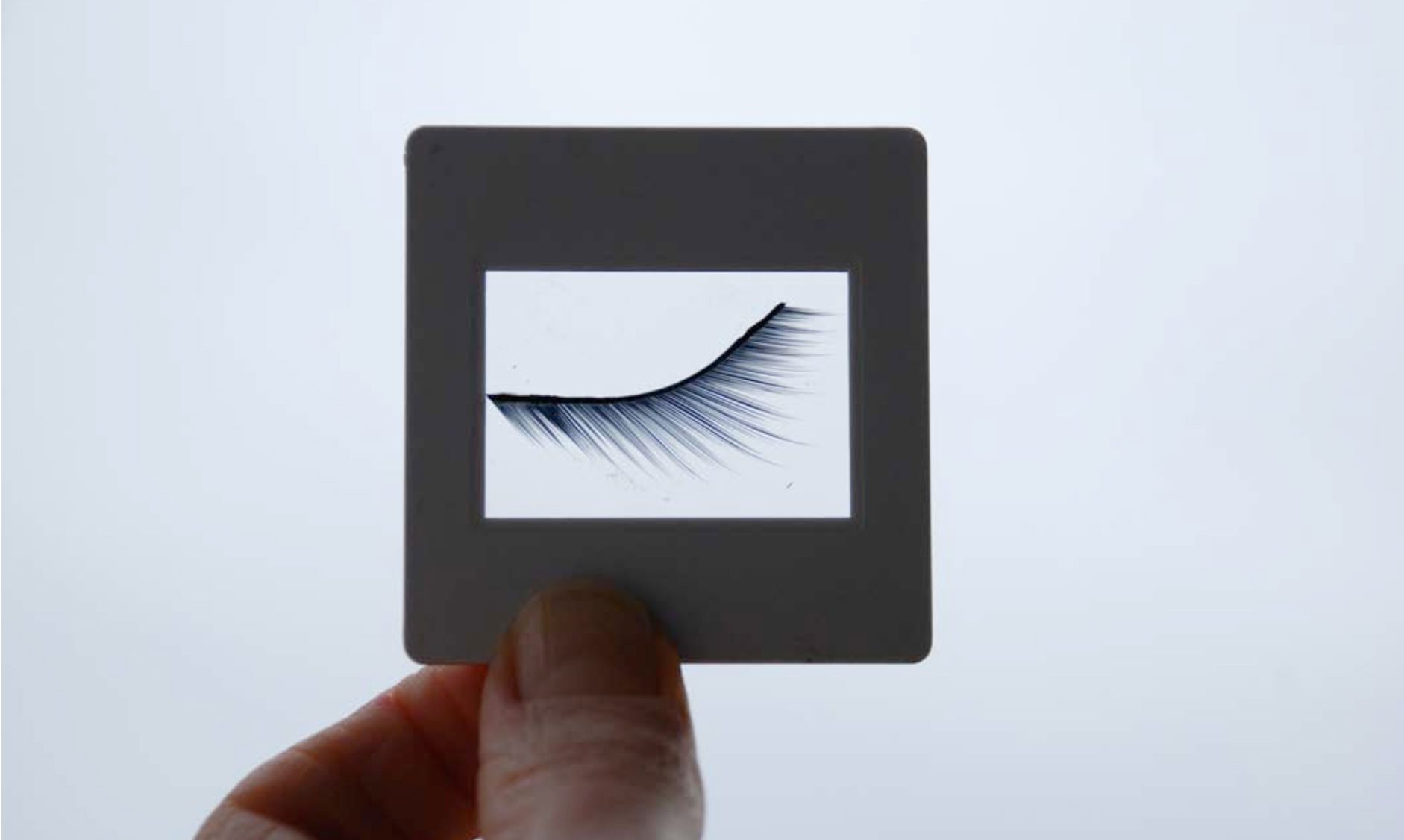

The video Tristeza documents an unsuccessful attempt to cultivate a blue orange and, in doing so, dwells on the duality of returning to the “Promised Land” and leaving it. The video – which explores pasts, presents and futures-that-could-have-been – is marked by a series of failures: to stay, “to return,” to sink roots, to create a blue orange. And yet, a blue orange, although not the one initially planned, eventually appears. Benbenisty’s private export of oranges does not succeed in transporting the citrus as an edible product. But the blue powder collected from the moldy peels of the “exported” fruit congeals into the primordial landscapes captured on the glass slides that make up the work Survey.

Silencing – titled after “gene silencing,” a process of regulating gene expression in a cell to prevent the emergence of certain traits – substitutes oranges floating on the surface of the Mediterranean for the Hebrew vowel markers (tenu’ot, vocal “movements,” in Hebrew) of the biblical ordinance in Genesis 12:1: “Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father’s house, unto a land that I will shew thee.” The Sea, the migratory opposite of the Promised Land, evokes perennial Zionist anxieties about potential destruction. The work frames the failure to fulfill the biblical prophecy, one of the main foundations of Zionist aspirations, as personal and generational: while Keren’s father adhered to the biblical ordinance, Keren erased it after an unsuccessful attempt to return that led to a new departure.

In Grafting, a series of collages made from 35mm slides taken by the artist’s father in the 1960s, Benbenisty mimics the horticultural technique whereby tissues taken from different plants are joined to create a hybrid species, sometimes a more robust species resistant to disease. In the collages, the fusion of the original photographs with a version in which the colors of the original have been inverted results in the selective replacement of orange with blue. The repair tape that holds the collaged pieces together alludes to the wax tape used to seal tree grafts.

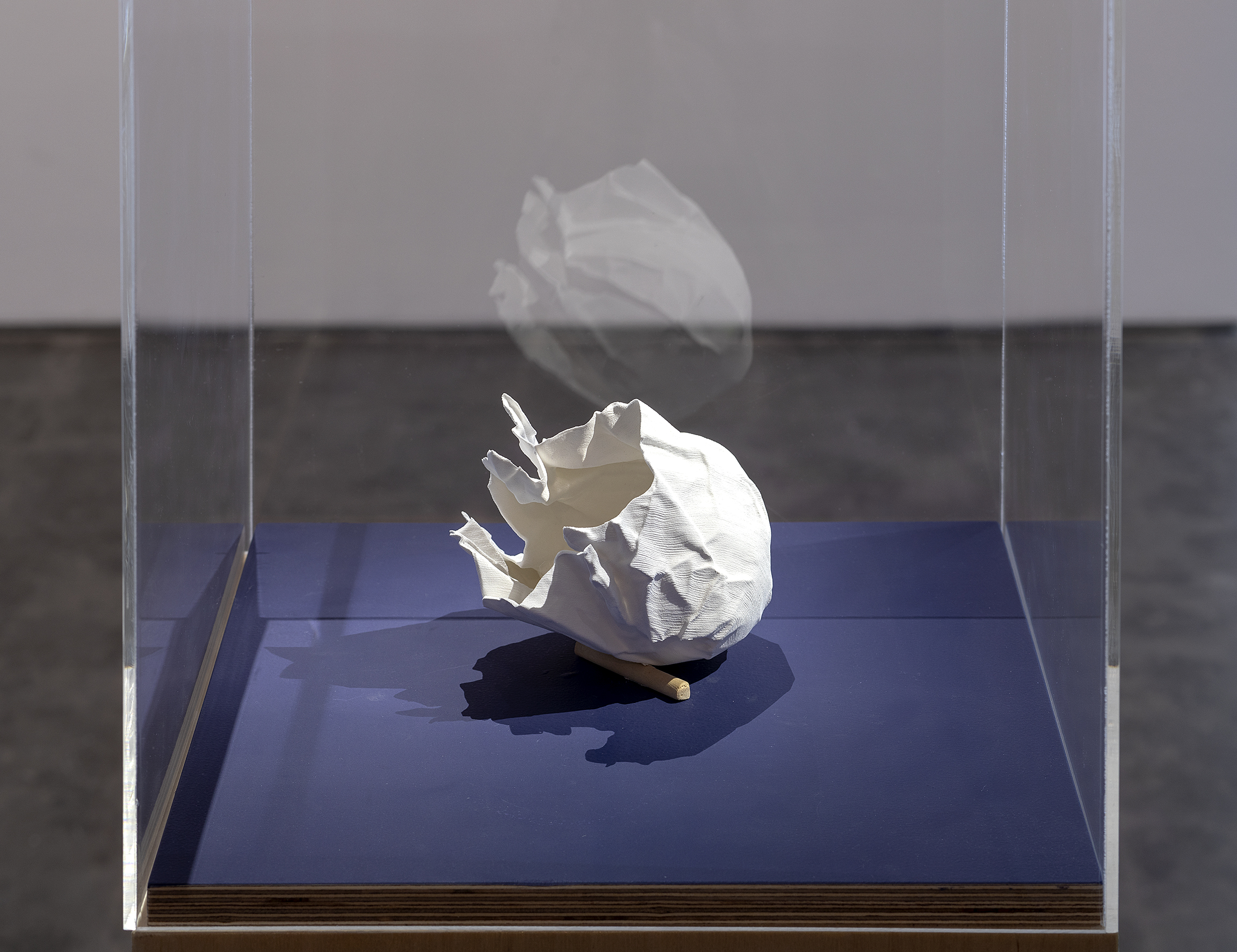

The 3D-printed sculpture Untitled recreates a piece of wrapping paper frozen in the form it assumed after wrapping an orange. The work serves as a relic of the lost orange, time and labor of Keren’s maternal grandmother, an immigrant from Morocco who worked in a packaging facility where oranges were prepared for their export from Israel.

The sense of failure and impossibility that threads through the works in the exhibition is the source of the melancholy, Tristeza, which also translates to “feeling blue. As opposed to the other forms of movement to and from the Promised Land, with their clear directionality, the melancholy is all-engulfing. Tristeza is perhaps the land we are shown.

G.B.

Tristeza, 2024, video still

Grafting (Orange tree, Re’hovot, Jan. 1968), 2023, hand-cut photographs, repair tape, 14 5/8 x 11 1/2 (framed).

Grafting #2 (Agrume), 2023, hand-cut photographs, repair tape, 11 5/8 x 9 1/2 (framed).

Grafting #3 (Agrume), 2023, hand-cut photographs, repair tape, 11 5/8 x 9 1/2 (framed).

Two-channel video animation, 6’20 sec, loop, 12” inch screens, 2019 (Vimeo)

Two-channel animation, shown on two separates screens, reveals the coordinates of the current location of Jaffa. Digitally reversing the images also reminds the viewer that the opposite color of orange is blue.

Bluranj

A film made out of an artist book, accordion structure 60 sheets with single gatefolds, hand glued

H.4 W.10 L.17 cm / Unfolded H.4 L. 600 cm. 2021-2022

Bluranj is an artist book composed of continuous 60 folded sheets – an assemblage of 60 images, folded and partly glued to each other. Each full page is a frame of footage I filmed in Israel between March 2020 to April 2021, composed of documentary and fiction materials, following the process in which an orange turns from orange to blue.

I spent the transformative year of the pandemic in Israel, after 22 years living in Paris and New York. There, I developed a body of work, Tristeza, named after the Tristeza Virus—a plant-based disease which has caused millions of citrus trees worldwide to die over the past 100 years. Tristeza is an ongoing project of my most recent research, including a film, an artist book and an object, outlining a conceptual inquiry that encapsulates my desire to create a blue orange tree as a way to stimulate and represent a deeper conversation on this fruit’s iconic and charged representation within Palestinian/ Israeli culture and society.

In 2017, I began my research on the popular Israeli Jaffa orange brand where I explored the duality of the orange symbol, inherent within Israel-Palestine culture and identity. In the early 19th century, the orange industry in this region was lucrative. Yet, within this economic trading, the orange quickly became affiliated and recognized as the ultimate Zionist symbol that signified working the land, as well as technological progress. As a result, Jaffa oranges became one of the quintessential symbols of the State of Israel, whilst also the emblem of the lost Arab-Palestinian land, a signification that has been erased entirely from the Israeli collective narrative.

During 2020, I expanded my research on transgenic plant engineering by following the work of researchers at the Volcani Agriculture Institute in the department for Enhanced Citrus Species. My goal was to change the DNA of the orange and reverse the color of the fruit into blue, and, possibly, creating a new species. Altering one of the most distinct symbols of this land and inventing a new strain, conceptually suggests a poetic read on the continuous conflict of identity politics in both nations.

The title of the book ‘Bluranj’ is a name I coined for the new imaginary species. It is a portmanteau of ‘blue’ and ‘orange’, with the addition of the letter “J” to mark the Sanskrit origin of the “orange” name— ‘naranj’. The fold at the core of the book’s conceptual demarche, generates a disrupted and fragmented reading. It hides as much as it reveals. It creates a new layout to record time. Browsing the book displays a 3D image that is composed out of three frames which are seen at the same time, creating a collage-like images.

Bluranj is about a color as much as it is about an orange. The fruit is a metaphor of a land and its people and the color, of a state, a condition. It unfolds the political, social and biological narratives and mirrors the “rotting, which is a privileged place of mingling, of the contamination of life by death, of begetting and of ending” (Julia Kristeva).

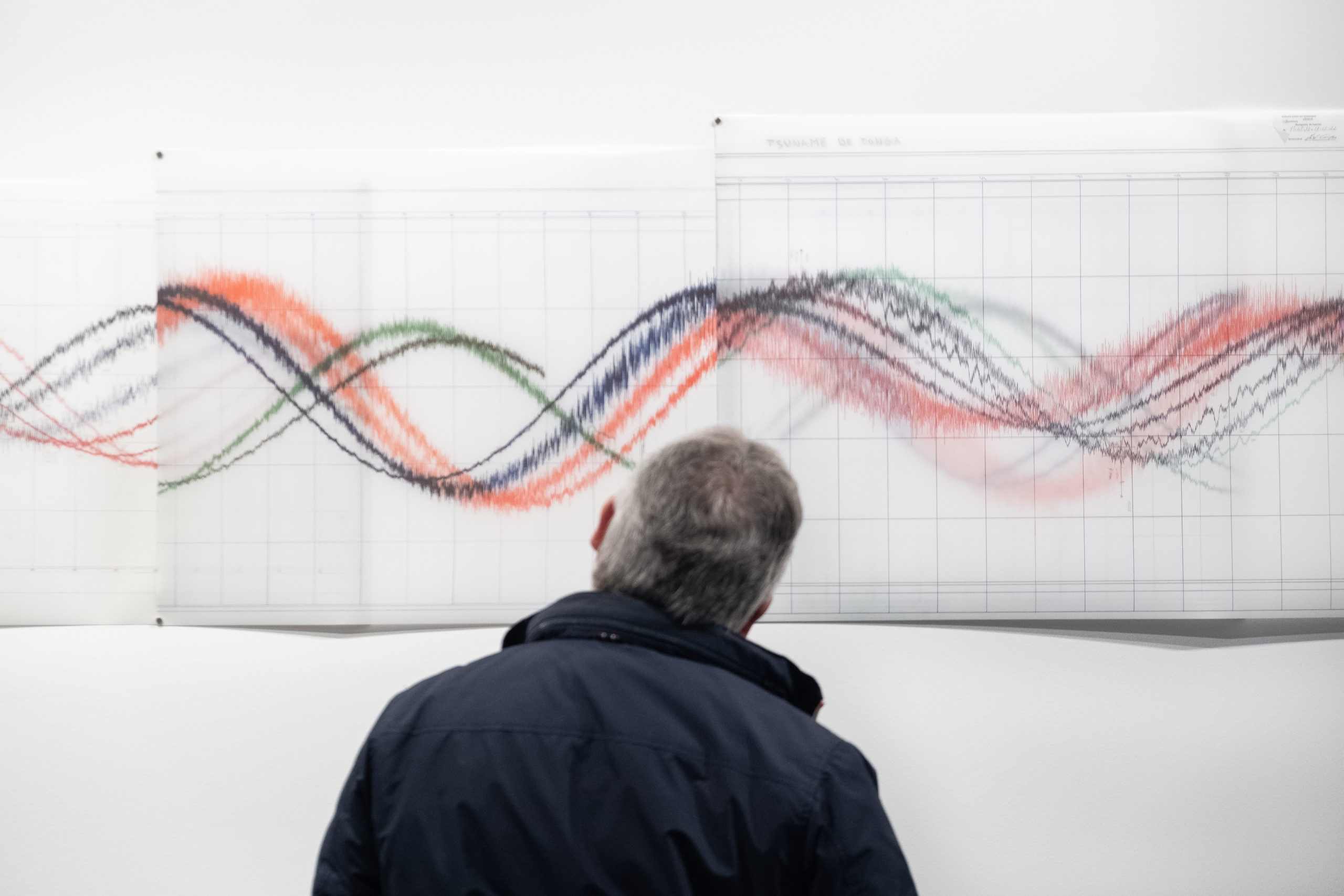

HD Video and sound, collaboration with João Pimenta Gomes, 6’21 min. Wall collage, tidal waves, semi-translucent film, variable dimensions. 2022 Vimeo link

In ‘We Belong to Gaia’ (2006), scientist James Lovelock imagines the Earth “like a kind of animal… like a planet that behaves as if it were alive… “Metaphor is important because to deal with, understand and even ameliorate the fix we are now in over global change requires us to know the true nature of the Earth and imagine it as the largest living thing in the solar system, not something inanimate like that disreputable contraption ‘spacecraft Earth’.

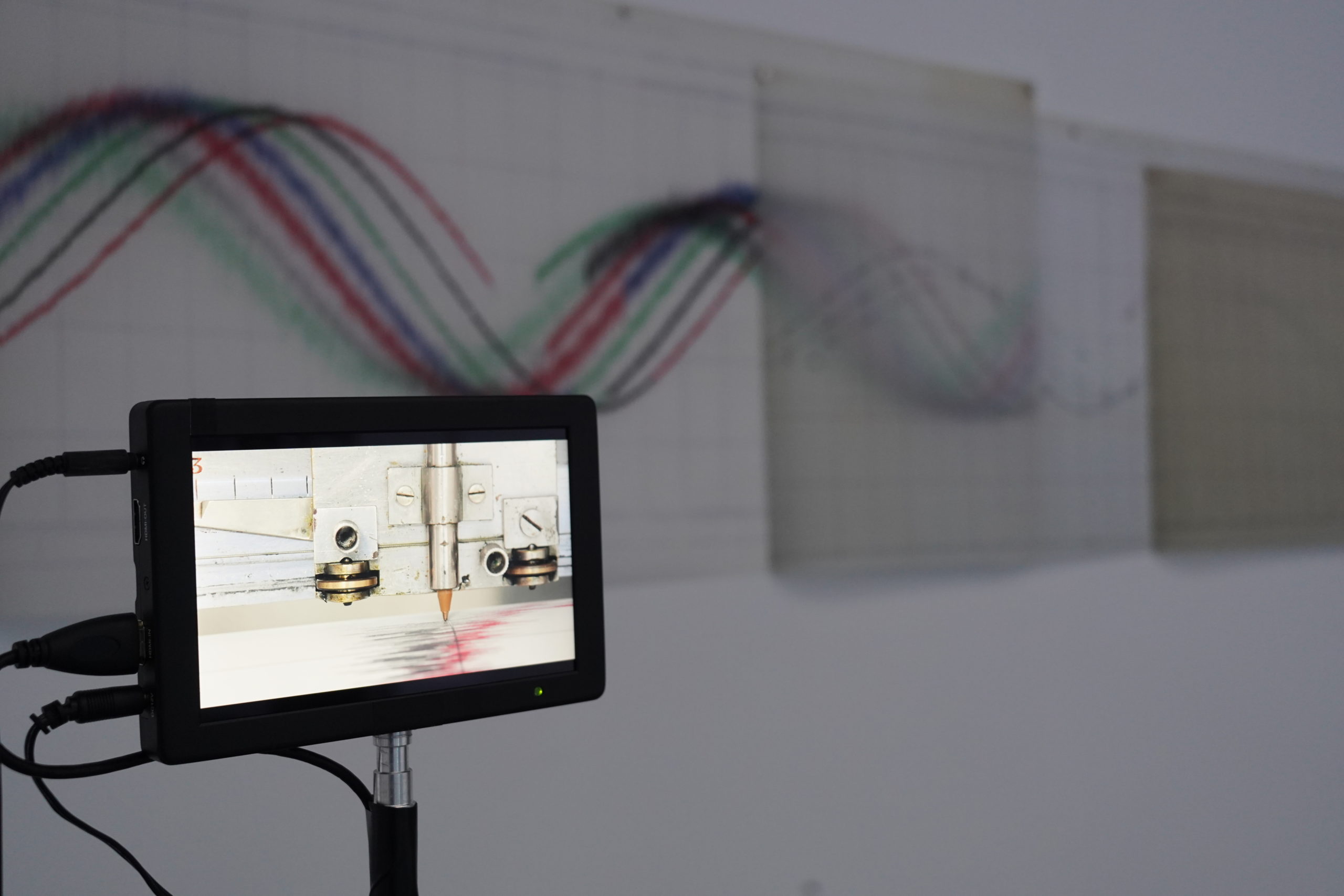

During her residency in Portugal, Keren Benbenisty looked daily at the ocean through the Cascais Tide-gauge, a 19th century device that records and plots changes in sea level live. Recorded analogically in the form of a tide chart, the data reflects events taking place thousands of kilometers with a time lag. Inspired by the thought of Lovelock, the artist wanted to translate these recordings, archived for more than a hundred years, into a score interpreted by a human voice, making the ocean a body “behaving as if it were alive.” The sound collage, which responds to the wall collage, is an act of translation and “embodiment” that underlines the complex relationship between man and nature in the time of the Anthropocene. Taken as a whole, the work bears witness to the relationships of interdependence that link not only the different regions of the world but also human beings to the living world, thus resisting the deleterious belief in the autonomy of beings and nations. The video, filmed inside the historical monument, the Maregrafo do Cascais, is a collaborative work with the artist João Pimenta Gomes who composed the sound piece from a score by the American composer Harry Partch, adding the voice of Portuguese Fado singer – Carminho.

Installation view, Les Labos d’Aubervillers, France

Installation view, Centro de Artes e Criatividade, Torres Vedras, Portugal

Sound performance by João Pimenta Gomes, Museu da Presidencia da Republica, Lisbonne, Portugal

Soloway Gallery is pleased to present Open the Land to the People, a solo exhibition by Keren Benbenisty. The exhibition presents selected works (2016-18) from Benbenisty’s study into the Lessepsian Migration of fish from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal, which slices through the Egyptian desert.

The Lessepsian Migration is named after Ferdinand de Lesseps, a French diplomat and the developer of the Suez Canal, which was constructed between 1859-1869. The canal was introduced to the world as the pinnacle of human progress, and a benevolent project that connects between East and West. In reality, the new waterway was designed to serve the trade interests of the European imperialist powers by allowing ships to sail directly between Europe and Asia without the need to round the African continent. After its opening in 1869, the new canal catalyzed a massive migration of marine species to the Mediterranean Sea, which brought significant changes to its ecosystem and biodiversity.

Benbenisty follows the work of the Tel Aviv University zoologist Dr. Menachem Goren, who appears in her video work Light, Skin (2017), and studies his methods and taxonomies to develop her own methodology. In On Black and White (2017), the artist removes the fish skin, processes it and transforms it into 35mm slides, indexed by coded skin tones of her own invention, which defy the scientific binary of black and white. In a series of prints titled This is Not a Fish (2017), the artist documents fish species by coating them in black ink and imprinting their form on paper by using the Japanese Gyotaku printing technique. Classified border-crossing stamps imprinted on the skin-thin Japanese paper (blue for a “Native” stamp; red for “Alien”) imbue the Magritte-referenced title with a disruptive stand against the crude indexicality of both migrating fish and humans. Benbenisty’s use of ink imprints extends to her large-scale painting Mare Nostrum (2016-19), which depicts a colossal folding wave that the artist painted solely by the use of her inked fingerprints.

Benbenisty’s critical intervention into the scientific discourse over the migration of fish provides for an insightful metaphor for the complex and painful issue of human migration that is stirring political unrest across Europe and the US. Aperire Terram Gentibus (Latin for “Open the Land to the People”) was Lesseps’s family motto, which later became the official motto of the Suez Canal. Against the backdrop of the current standoff in US politics over the country’s immigration policy, it bears mentioning that Lesseps was also the diplomat who was chosen to present the Statue of Liberty as a gift from his country to the US under its original title and intent: “Liberty Enlightening the World”.

* This exhibition was made possible with the help of The Foundation for Contemporary Arts’ Emergency Grant.

Installation, works on paper, orange peels and ink. 2021

I spent the transformative year of 2020 in Israel. There, I developed a body of work, Tristeza, named after the Tristeza Virus—a plant-based disease which has caused millions of citrus trees worldwide to die over the past 100 years. The name Tristeza, which means sadness in Spanish and Portuguese, was coined in the 1930s by a Brazilian farmer who helplessly watched the trees in his orchard gradually decline. Tristeza is an ongoing project of my most recent research, including a film, outlining a conceptual inquiry that encapsulates my desire to create a blue orange tree, Bluranj, as a way to stimulate and represent a deeper conversation on this fruit’s iconic and charged representation within Palestinian/ Israeli culture and society.

In 2017, I began my research on the popular Israeli Jaffa orange brand where I explored the duality of the orange symbol, inherent within Israel-Palestine culture and identity. In the early 19th century, the orange industry in this region was lucrative. Yet, within this economic trading, the orange quickly became affiliated and recognized as the ultimate Zionist symbol that signified working the land, as well as technological progress. As a result, Jaffa oranges became one of the quintessential symbols of the State of Israel, whilst also the emblem of the lost Arab-Palestinian land, a signification that has been erased entirely from the Israeli collective narrative.

I expanded my research on transgenic plant engineering by working with scientists at the Volcani Agriculture Institute in the department for Enhanced Citrus Species. My goal was to change the DNA of the orange and reverse the color of the fruit into blue, promoting the creation of a new species, a hybrid, a mutation of Blue and Orange. Altering one of the most distinct symbols of this land and inventing a new strain, conceptually suggests a poetic read on the continuous conflict of identity politics in both nations.

The concept of this metamorphosis of the oranges can also be seen as a metaphor for what we experienced during the pandemic. Around the time in which the Tristeza virus first appeared, in 1929, the surrealist poet Paul Éluard published his poem The Earth Is Blue as An Orange. This coincidence greatly resonated with me while I embarked on this project. I found an organic link between the metaphor of the blue orange to last year’s pandemic. The accelerated shift occurring on a planetary level, where the familiar transformed and became alienated, seemed to find a correspondence with the shift of color of the orange.

Bluranj is a name I coined for the new species. It is a portmanteau of blue and orange, with the addition of the letter “J” to mark the Sanskrit origin of the “orange” name—‘naranj’. It takes five years to create a new citrus species, which is said to be the time it takes people to acclimatize to a new environment. It might be also the time necessary for the surreal bluranj trees to become real. This project is ongoing, until I set the roots of Bluranj trees, to offer a new view in the landscape where they will be planted.

—Keren Benbenisty

Ulterior Gallery, New York, NY

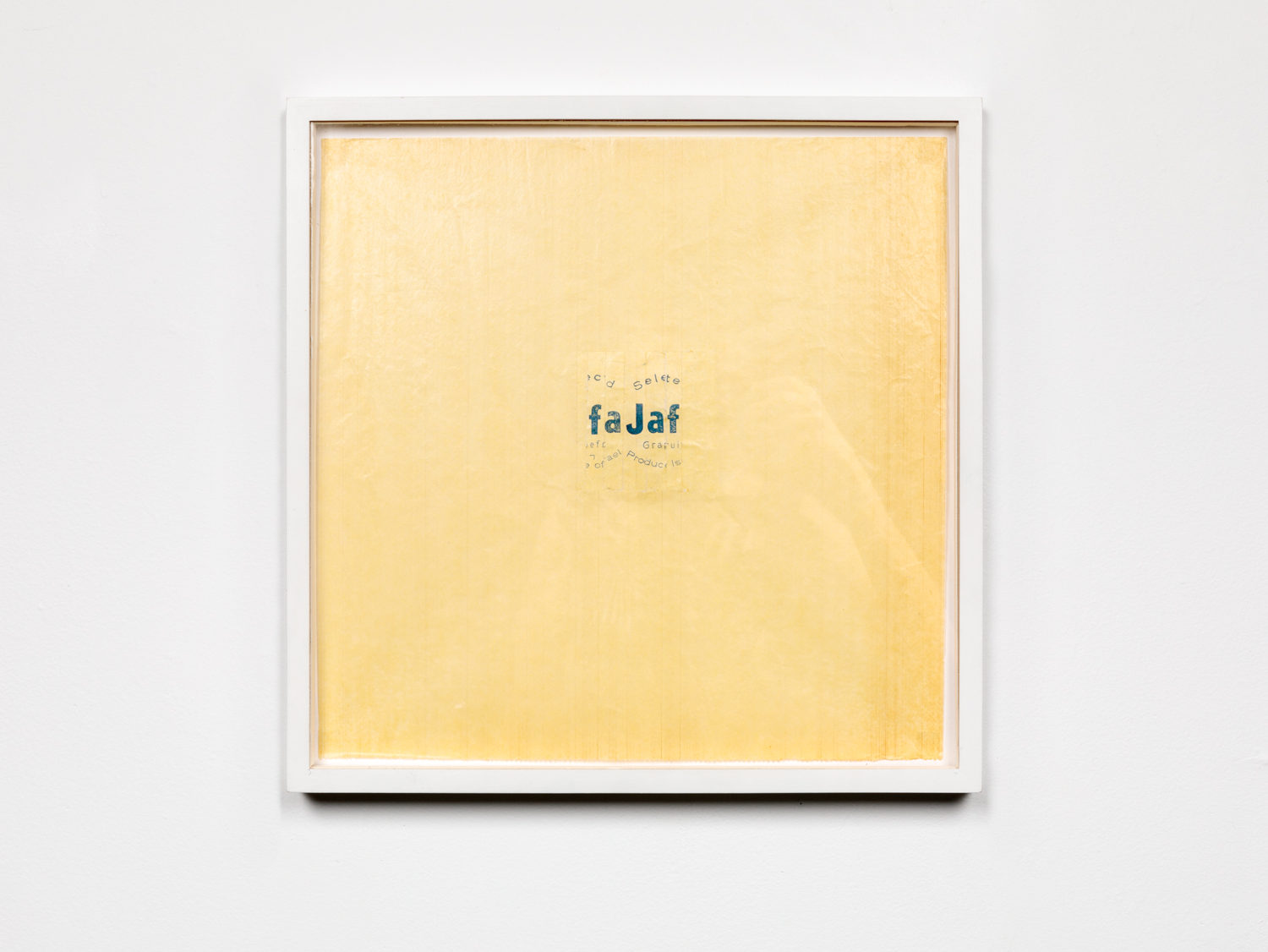

Tristeza, 2020. Wood, paper, ink and pencil. 15 3/4 x 11 3/4 in. / 30 x 40 cm.

Ulterior Gallery, New York, NY

365 Days in Jaffa, 2020/21. 365 Orange peels, ink. Variable dimension.

Untitled, 2021. An erased page from a vintage book, orange peels and ink. 11.3/4 x 15 1/4 in. / 30 x 39 cm.

Untitled, 2021. An erased page from a vintage book, orange peels and ink. 11 3/4 x 15 1/4 in. / 30 x 39 cm.

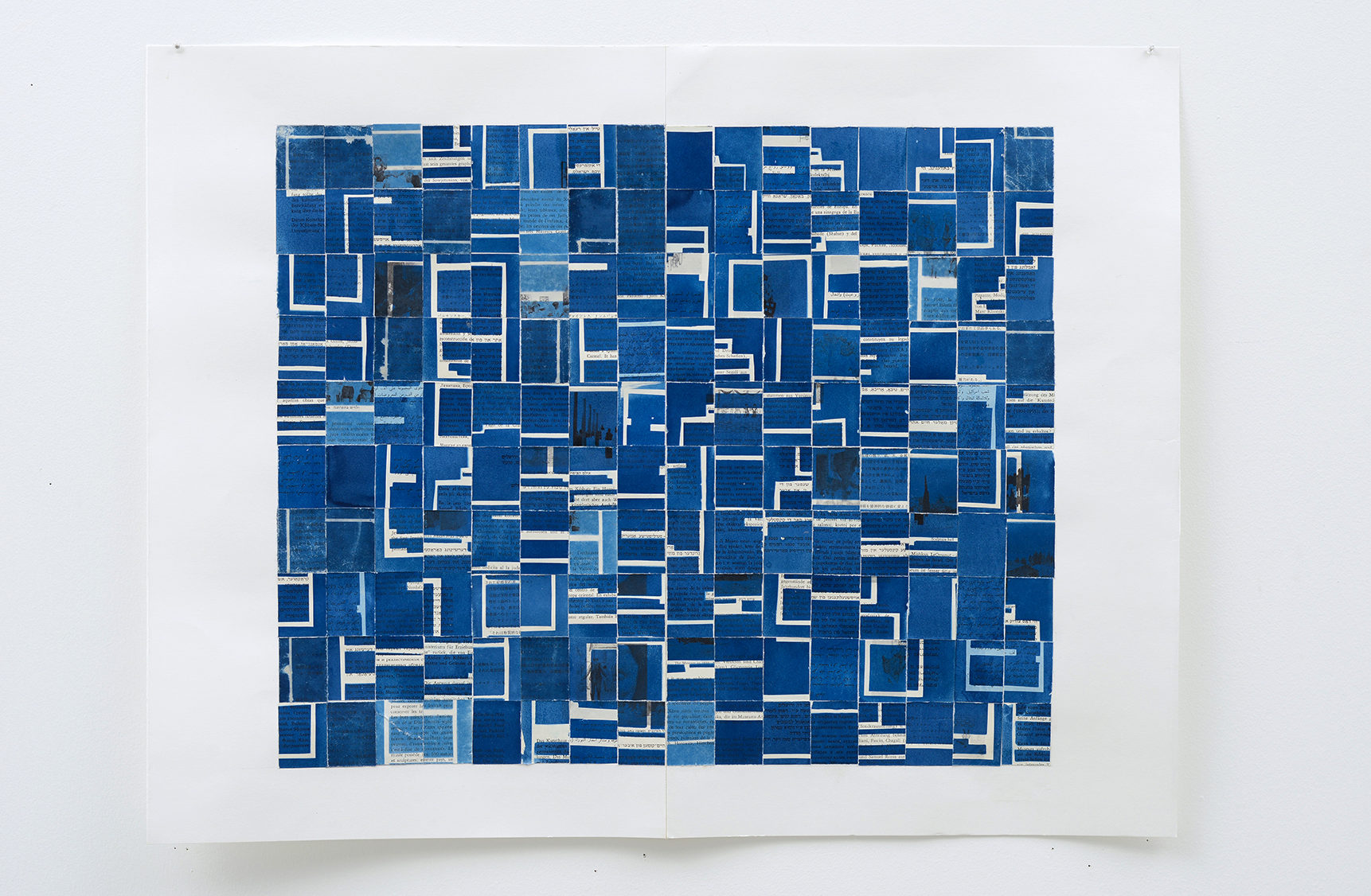

Oasis of Labor (Neve Amal), 2020-2021

52 pages from Ha’aretz and International edition of the NYTimes, ink, gesso, matt medium and blue carbon paper engraving.

21.5 x 22 in. (each)/ 55 x 36 cm. 88 x 189 in. / 223 x 480 cm (wall installation).

Tristeza, 2020. Ink on digital archival print, 13 x 18 1/2 in. / 33 x 47 cm.

Untitled, 2021. inkjet print, blue tape and glass. 10 x 12 in.

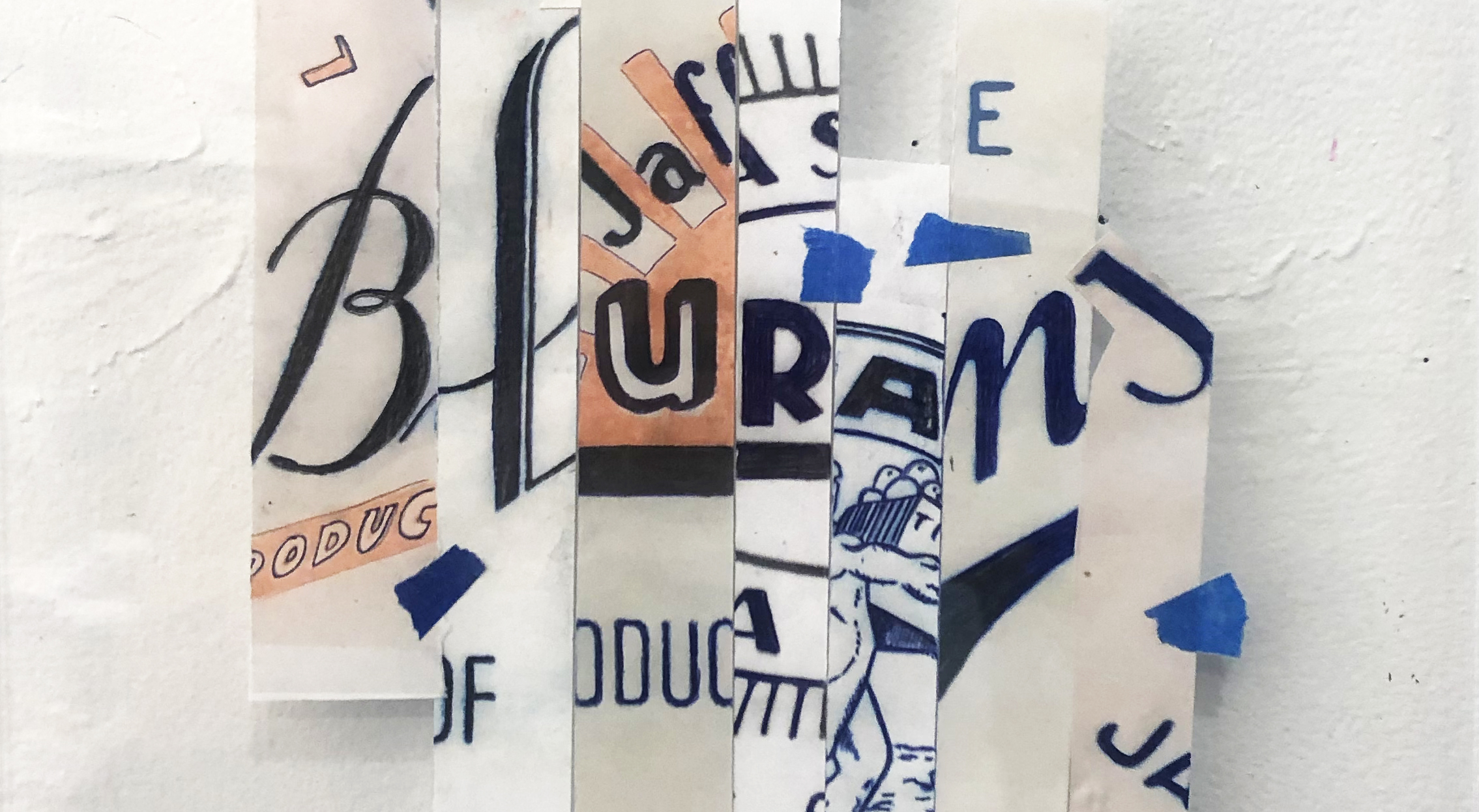

A series of collages, inkjet prints and blue tape, placed in-between glass sheets. 10″x12″ in. (each) 2020

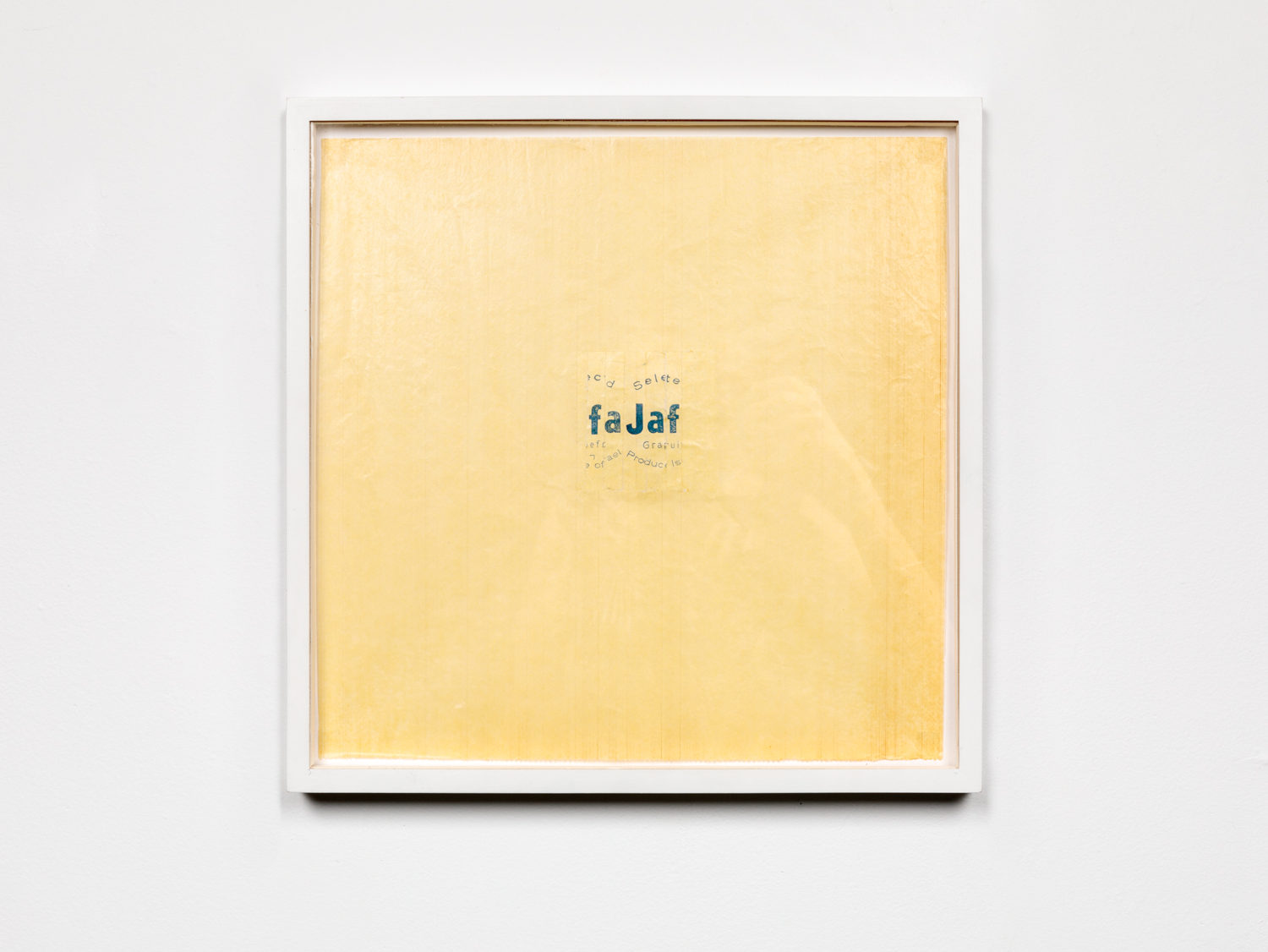

A series of blue carbon paper engraving and collages on food wrapping paper. 12″ x 12″ in. 2019.

A series of 26 works on paper; collage; two-channel video-animation on 12” inch screens, 2019/2021

Based on historical printed matter, archival materials, and contemporary geographical data, this body of work recalls the relationship between typography and topography through the concept of ‘revolving’, a recurring element in my work emphasizing change (from the Latin word revolver).

Following the rules of Verlan, a type of French slang, the word in the collage—”faJaf”—is a result of reversing the syllables of the word “Jaffa,” an iconic and politically charged brand of oranges that is also the name of a Palestinian city that has now been absorbed into Tel-Aviv. It produces a meaningless word that, like an erasure mark, signifies an attempt to correct.

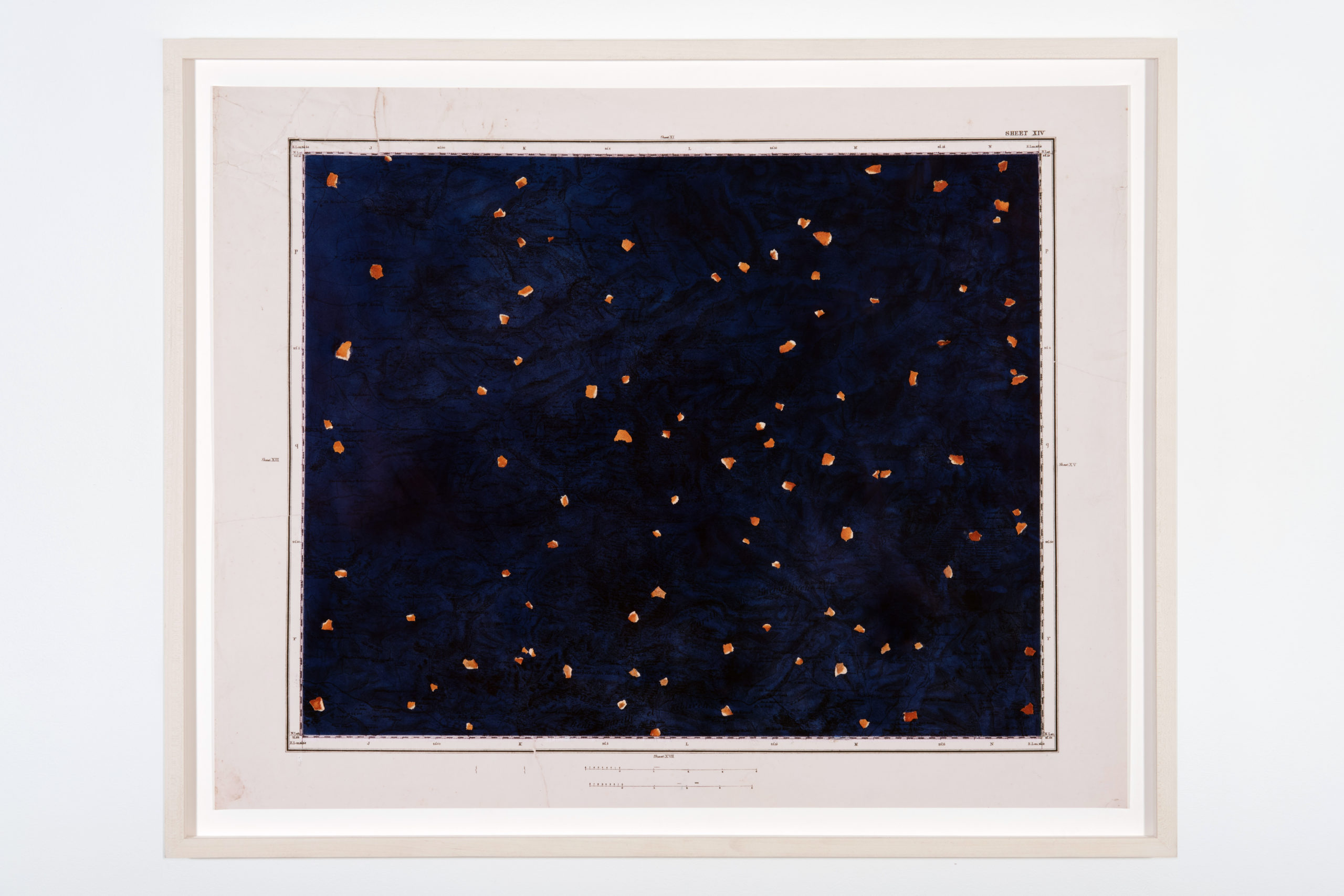

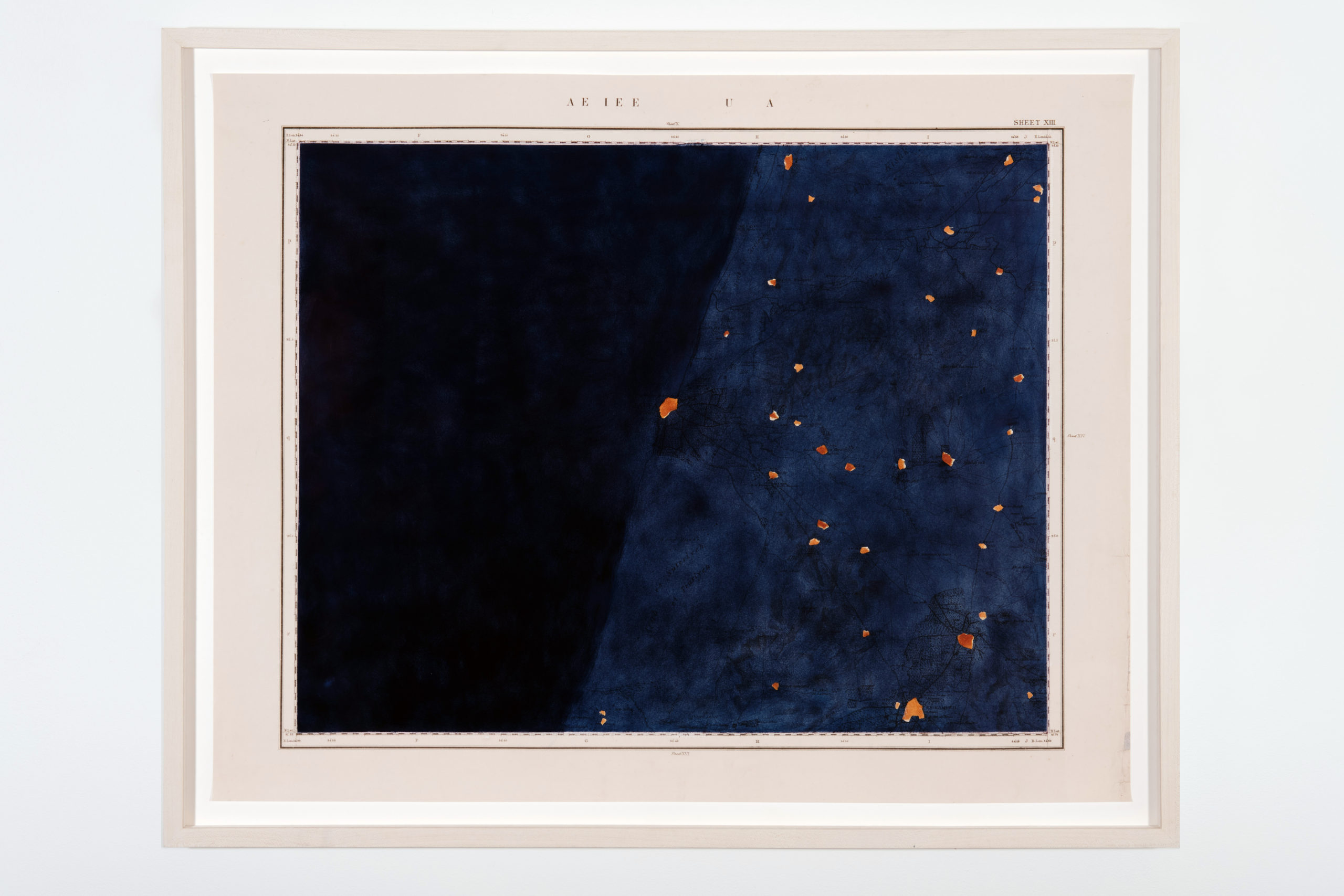

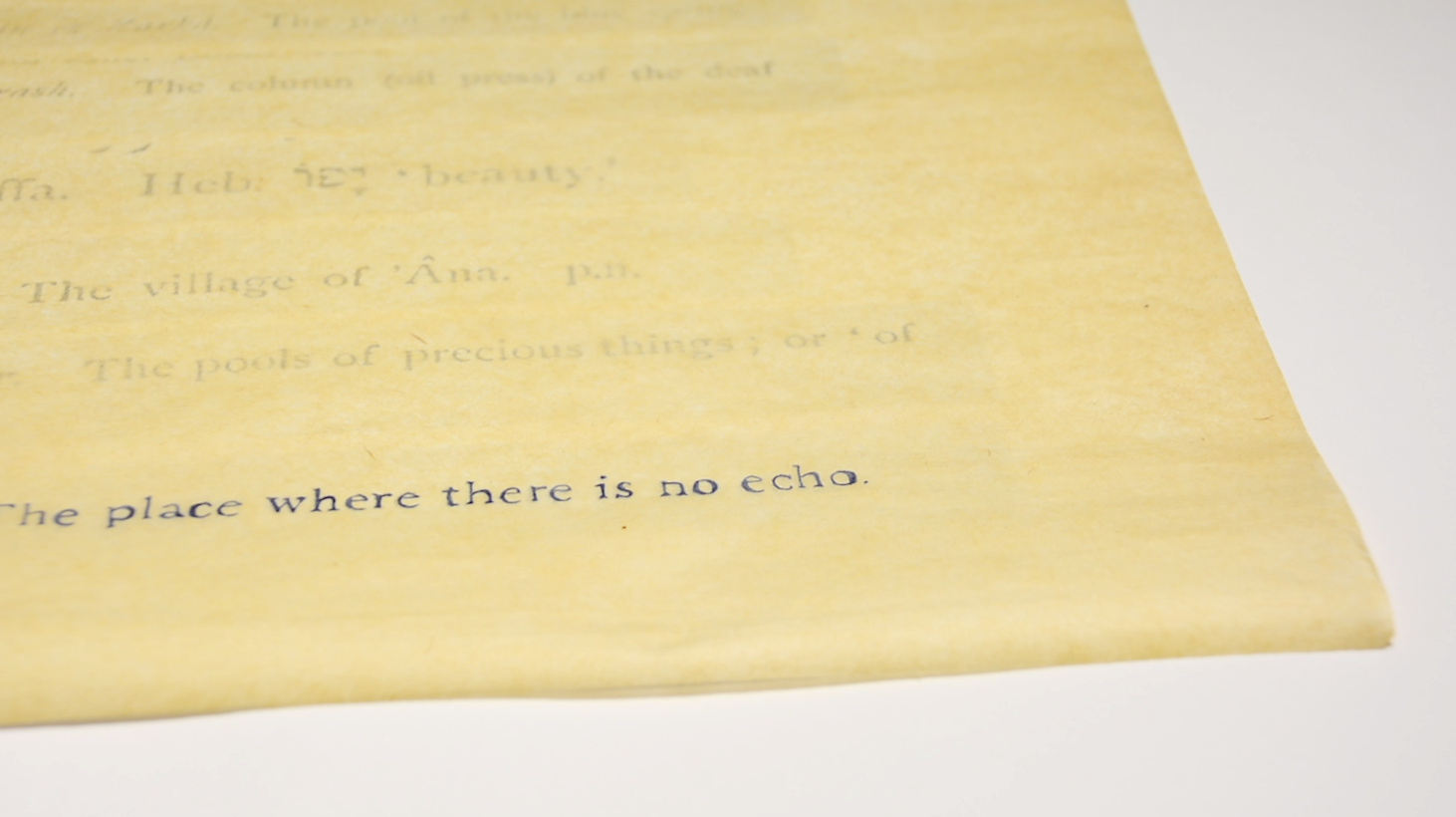

The complete mapping project, a product of the ‘Palestine Exploration Fund’ between 1881 and 1887 as part of ‘The Survey of Western Palestine’, comprised 26 maps. In this project, I printed each map at its original size, then erased it. I manually coated it with Prussian blue pigment, rubbed onto the paper. Every place whose name has been changed since the maps were produced is marked with an orange peel that is glued to the paper and covers the location in question. The gestures of erasure and mark-making not only blur the scientific data underpinning the work of the cartographers but also transform the earth into the sky; the maps become abstract images, challenging the nature of cartography and resembling celestial charts.

The work’s title is taken from a book part of the PEF Survey; it provides the translation and meaning of all Arabic place-names appearing on the maps. The printing, marking, and erasing techniques echo the methodical and thorough efforts that took place (and continue today) to Hebraicize Arabic place-names in Israel. The erasure of local histories and identities of the place has long been part of the Zionist project and has served to imprint its ideology on the land.

Untitled XIV, Archival digital print, Prussian Blue dry pigment, orange peels and glue (detail)

Untitled XIV, Archival digital print, Prussian Blue dry pigment, orange peels and glue (detail)

Untitled XIV, Archival digital print, Prussian blue oil pigment, orange peels and glue, 26″ X 32″ in.

Untitled XIV, Archival digital print, Prussian blue oil pigment, orange peels and glue, 26″ X 32″ in.

Untitled XIII, Archival digital print, Prussian Blue dry pigment, orange peels and glue, 26″ X 32″ in.

Untitled XIII, Archival digital print, Prussian Blue dry pigment, orange peels and glue, 26″ X 32″ in.

Untitled XII, Archival digital print, Prussian Blue dry pigment, orange peels and glue, 26″ X 32″ in.

Untitled XII, Archival digital print, Prussian Blue dry pigment, orange peels and glue, 26″ X 32″ in.

Untitled X, Archival digital print, Prussian Blue dry pigment, orange peels and glue, 26″ X 32″ in.

Untitled X, Archival digital print, Prussian Blue dry pigment, orange peels and glue, 26″ X 32″ in.

N. E., Two-channel-video animation, 6’20, loop

N. E., Two-channel-video animation, 6’20, loop

4K Video and sound, 4’45 min (loop). Collaboration with Tomas Moravec. 2018

Video-performance filmed on a site located at Holešovice, Prague. Archival images show a paint factory in the 19th century that later became the Center for Geology Research. The last building was demolished in 2012 with intention of a new construction site. Similar to the Tower of Babel, the intended project was stopped by the authorities due to restrictions on the height of the buildings in that specific area. Filmed with a drone, the video shows three actions happening at the same time. Marking stones with numbers, measuring the height, length and diagonal of the pit and the drone cameraman documenting slowly from a birds-eye-perspective.

A series of collages made with cyanotypes and pages from the original publication of the museum (1970). A series of carved stones, ink, water. Made in collaboration with Aiman Zreiqi. Ein Harod Museum, IL. 2019

Master Plan, Mother Tongue is a two-part installation that explores the often-overlooked relationship between text and architecture through particular material fragments from the history of the Mishkan Le’Omanut. While any architectural drawing can be understood as a document that translates a three-dimensional structure into a two-dimensional medium, a master plan is distinct in that it not only details an existing structure but also provides a practical and conceptual framework for future growth by subsequent builders. In this sense, the Hebrew phrase for master plan, father plan (Tochnit Av), is particularly apt in its generative associations.

For her project, Benbenisty selected a catalogue of the museum’s collection remarkable mostly for the number of languages it contains—ten in all. A brief description of the museum, its history, mission, and holdings can be found in Arabic, English, French, German, Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian, Spanish, Japanese, and, perhaps most surprisingly, Esperanto. Treating the catalogue pages as sculptural material, Benbenisty has literally carved into the printed words of these many languages, then layered and recombined them until they lose their semantic meanings. She then covered these layered compositions in light sensitive solution and exposed them to the sun, transforming them into cyanotypes, recalling the process through which architectural blueprints are produced.

Master Plan, Mother Tongue focuses less on the intermedial translation from text to architecture than the difficult translation of a utopian project from paper to real time and space, whether it be the Mishkan, Ein Harod, or the Zionist project writ large. Kafka repeatedly addressed the impossibility of achieving utopia in his writing. His rumination on the Pit of Babel, published in Parables and Paradoxes, replaces the act of building with digging, thereby reversing the vertical thrust of the original story. By bringing Babel back down to earth, Kafka evocatively illustrates how the transcendent unity of the tower, which embodies the ideal of a single, universally understood language, is only materialized in heterogenous, subterranean mazes that imperfectly intersect, overlap, and remain forever incomplete. In returning to the Mishkan’s catalogue as the source for Master Plan, Mother Tongue, there is a particular irony that this multilingual flurry occurred in Israel—a state whose majority-Jewish inhabitants are almost entirely descended from immigrants who were discouraged from speaking their native languages in favor of the recently secularized and reinvented Biblical language of Hebrew. To speak only Hebrew was in a sense to “speak with the same lip,” as the Bible describes the builders of the Tower of Babel before God’s punishment. The universalist gusto which led to the translation of the Ein Harod catalogue into as many languages as possible occurred only later in 1970, after the Hebrew language had become entrenched, replacing old diasporic languages as the mother tongue of the new Israeli population.

Chelsea Haines (excerpts from the catalogue essay)

Installation views, 14 Interpretations, curated by Yaniv Shapira and Tal Gelfer at Mishkan Ein Harod Museum, IL

(Photo credit Elad Sarig)

2008-Ongoing. Black ink engraved on brass plate, variable dimension. Edition of 1+1 AP.

Since 2008 I collect headlines from daily newspapers. Printed every day in mass production and update frequently on the internet edition, the short-lived headlines are a basic transmission tool delivering the most important global news. The running events, such as time, rapidly changing, mark our present and future realities. Despite their ephemeral side, the content has an eternal impact, which reinforces the relation between past, present and future.

The selected headlines in this project represent a poetic language often used in a capitalist consumer culture, personalizing the non-private matter. The political becomes personal and generate an effect of solidarity and identification. The gap between the meaning of the headline and the content of the article is sometimes as extensive as its interpretation. Each headline, engraved on a brass plate, similar to signals in public places, perpetuates the message and become a commercialized object. The lack of source or context, transforms the political or social worldwide event into a poetic micro-message.

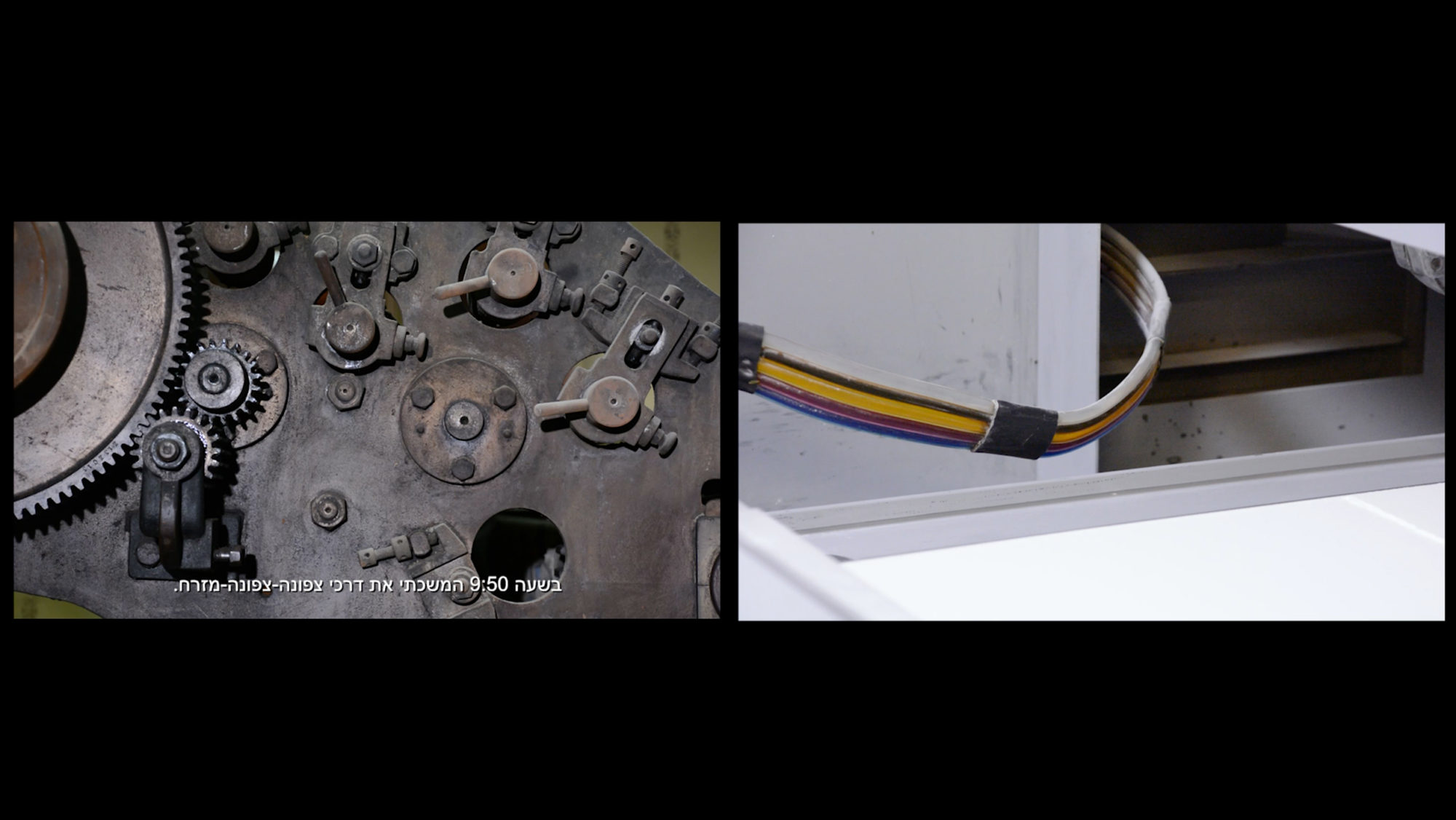

Two-channel video and sound installation, 12′ min, 2 LCD screens 55″ mounted on two poles. 2018 (Vimeo)

In her project Fajja, which takes its name from a Palestinian Arab village depopulated in 1948, whose land is currently part of Petach Tikva, Keren Benbenisty explores the relationship between typography and topography. The printing press that inspired the project—one of the only two specimen still in existence—was built in 19th-century Germany and imported to Petach Tikva by Jewish settlers in 1932, where it was used to print paper for orchard owners to wrap Jaffa oranges until the 1990s. The Jewish immigrants who settled in Palestine in the early 20th century turned Jaffa oranges—a species cultivated by Palestinian farmers in the mid-19th century—into one of the country’s primary exports. After 1948, the citrus production became established and expanded from Jaffa to other places in the country, among them Petach Tikva, which became a major orange exporter. An emblem of the lost Arab-Palestinian land, Jaffa oranges became one of the quintessential symbols of the nascent State of Israel.

In her two-channel video installation The Place of the Fold, Benbenisty overlays images of the printing press with excerpts from Victor Guérin’s book Geographical, Historical, and Archaeological Description of Palestine (1868), which documents Arab villages in the area that have since disappeared. The second screen features a 3D printer, printing an object (Untitled) from white powder, superimposed with an image of Benbenisty’s hands printing a series of drawings (Land of Blue Oranges) on sheets of paper used to wrap Jaffa oranges, which she inherited from her grandmother—a citrus packer. In the drawings, the artist uses printing stamps made of orange peels covered in blue ink, juxtaposed with English translations of the names of disappeared Arab villages excerpted from Edward Henry Palmer’s Survey of Western Palestine (1881).

The Fajja project evokes a printing machine that erases as it names. In each of these printing processes, Benbenisty revives places and symbols that have been overwritten through the years by layers upon layers of written text. The printed surface of a map or an orange wrapper reveals how historical projections, colonial manipulations, and orientalist imaginations imprint and modify territories, as typographical interventions produce new topographies.

Raphaël Sigal

Two-channel video & sound installation, 5’ 30 min. 2018

Radiogardase-Cs contains ferric hexacyanoferrate(II) [Prussian blue insoluble] and is used as an anti-dote at contamination of radioactive cesium.

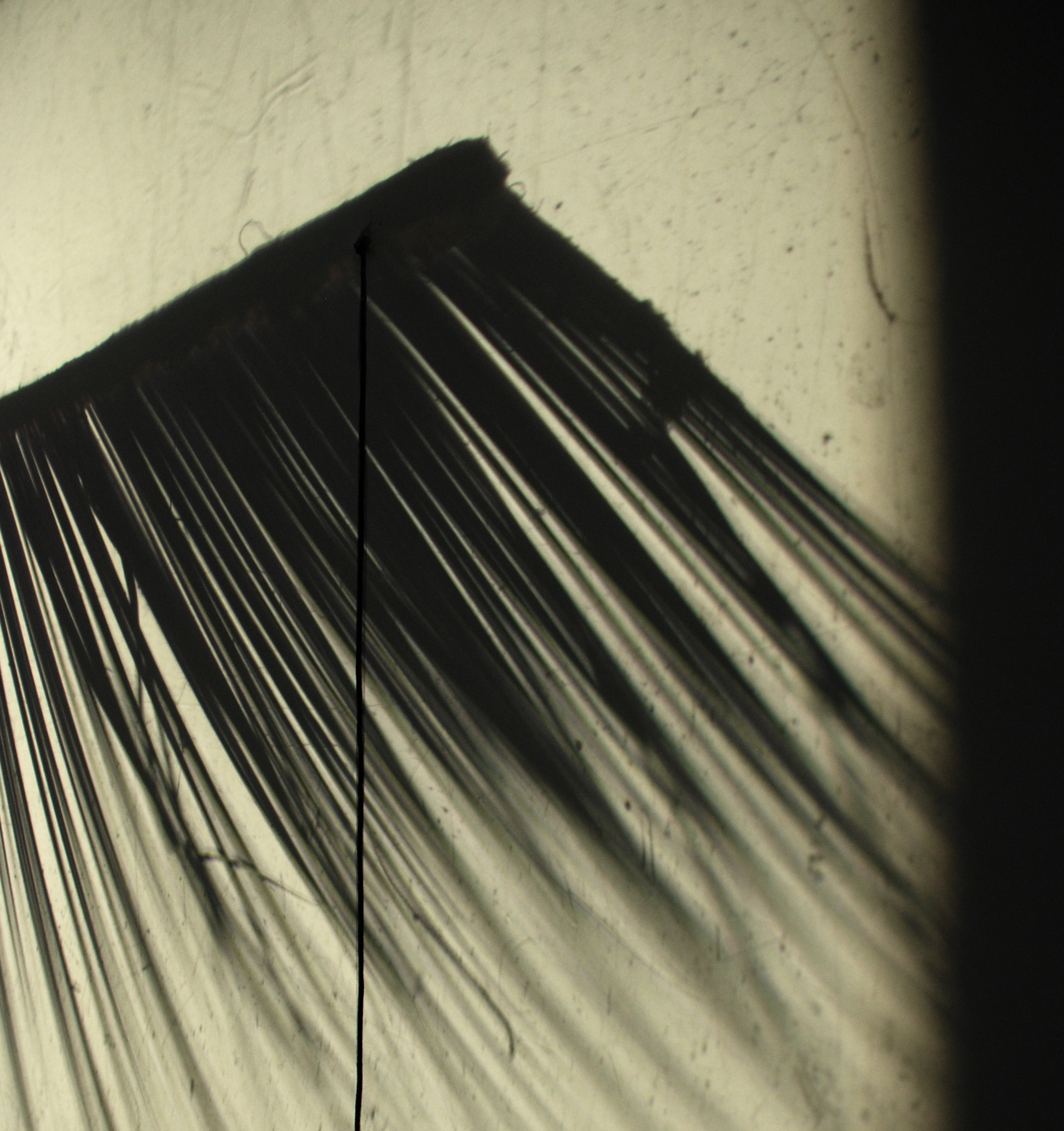

8mm (Silk)film transfer into HD video, 10’ min. 2017

Imago is an immersive HD video projection of a silk thread filmed through an 8mm projection. The floor-to-ceiling projection features a microscopic image of the thread throughout the moment the thread is decomposed by the heat of the projector and vanishes.

Two-channel video and sound installation; a series of 60 drawings, blue ink on original Jaffa Oranges wrapping paper; 3D-printed object. Collection gallery, Petach Tikva Museum, IL. 2018

In her project Fajja, which takes its name from a Palestinian Arab village depopulated in 1948, whose land is currently part of Petach Tikva, Keren Benbenisty explores the relationship between typography and topography. The printing press that inspired the project—one of the only two specimen still in existence—was built in 19th-century Germany and imported to Petach Tikva by Jewish settlers in 1932, where it was used to print paper for orchard owners to wrap Jaffa oranges until the 1990s. The Jewish immigrants who settled in Palestine in the early 20th century turned Jaffa oranges—a species cultivated by Palestinian farmers in the mid-19th century—into one of the country’s primary exports. After 1948, the citrus production became established and expanded from Jaffa to other places in the country, among them Petach Tikva, which became a major orange exporter. An emblem of the lost Arab-Palestinian land, Jaffa oranges became one of the quintessential symbols of the nascent State of Israel.

In her two-channel video installation The Place of the Fold, Benbenisty overlays images of the printing press with excerpts from Victor Guérin’s book Geographical, Historical, and Archaeological Description of Palestine (1868), which documents Arab villages in the area that have since disappeared. The second screen features a 3D printer, printing an object (Untitled) from white powder, superimposed with an image of Benbenisty’s hands printing a series of drawings (Land of Blue Oranges) on sheets of paper used to wrap Jaffa oranges, which she inherited from her grandmother—a citrus packer. In the drawings, the artist uses printing stamps made of orange peels covered in blue ink, juxtaposed with English translations of the names of disappeared Arab villages excerpted from Edward Henry Palmer’s Survey of Western Palestine (1881).

The Fajja project evokes a printing machine that erases as it names. In each of these printing processes, Benbenisty revives places and symbols that have been overwritten through the years by layers upon layers of written text. The printed surface of a map or an orange wrapper reveals how historical projections, colonial manipulations, and orientalist imaginations imprint and modify territories, as typographical interventions produce new topographies.

Raphaël Sigal

Land of Blue Oranges, a series of 60 drawings, Blue ink on original Jaffa Oranges wrapping paper.

The Place of the Fold, Two-channel video and sound installation, 12′ min. French voiceover, Hebrew and English subtitles.

Untitled, 3D-printed object

Land of Blue Oranges, a series of 60 drawings, Blue ink on original Jaffa Oranges wrapping paper.

Land of Blue Oranges (detail), a series of 60 drawings, Blue ink on original Jaffa Oranges wrapping paper.

Installation views, Fajja, curated by Raphael Sigal at the collection Gallery, Petach Tikva Museum, IL (Photo credit Elad Sarig)

Kinetic installation, pump, blue ink, water, porcelain, glassware, pedestal, variable dimensions. 2014

Water, has been a consistent theme in my work over the past decade. In Avec Le Vide, Les Pleins Pouvoirs, (With the void, Full powers) I created a running fountain on a pedestal through which circulated pigmented water, a work which looked at the way in which Moorish design has been translated into European design Duralex glassware but also at the color blue, which was famously adopted and patented by Yves Klein.

The title of the fountain referring to a note left by Albert Camus at Yves Klein exhibition Vide at Iris Clert Gallery in 1958. During the opening night , a blue drink prepared by the bar of La Coupole in Montparnasse (a combination of gin, Cointreau, and methylene blue) was served to the 3500 attendees, who apparently ended up urinating blue the next day (much to the artist’s delight).

Kinetic installation; 1RPM motor mounted on a car beacon behind a screen, digital video slide projection, 1 hour (60 images) H.7′ L.8′ ft. H.213 L.243 cm; Drip system, 1RPM motor, black ink, water container, screen, artificial lashes mounted on 35mm blank slide, single-slides projector, H.4′ L.6’ft. H.120 L.180 cm. 2011

Two Suns in The Sunset

Two Revolutions Per Minute

Cut Black vinyl on the gallery window, street view.